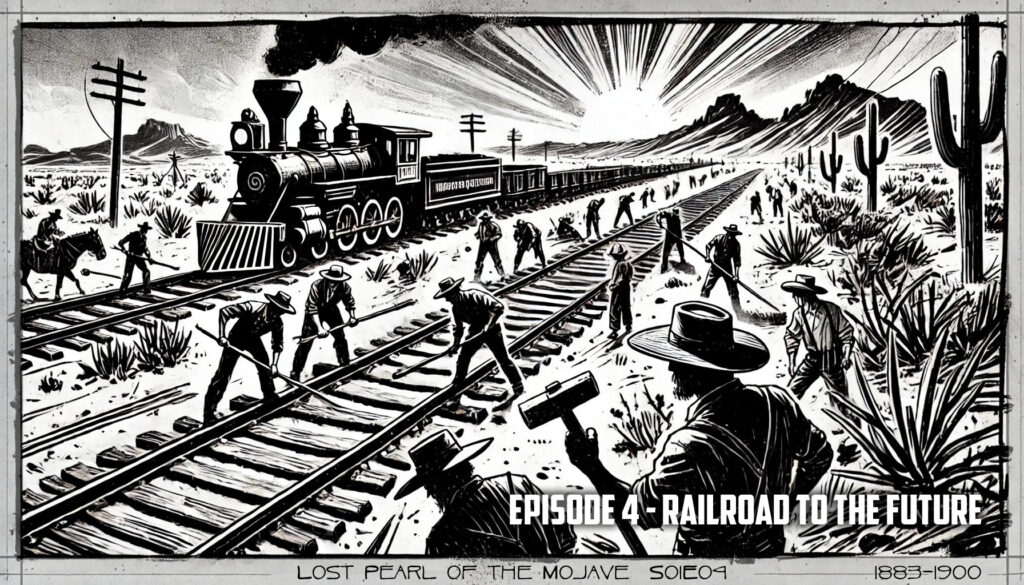

THE LOST PEARL OF THE MOJAVE – EPISODE 4

Railroad to the Future 1883-1900

EXT. BARCO PLATEAU TOWN – DAY (1885)

SCREEN OVERLAY: “Barco Plateau – 1885”

The sun scorches the high-desert sky, casting long shadows across the rising town. Barco Plateau is transforming—new brick and timber buildings ring the dusty square. A blacksmith hammers at iron. A woman strings laundry between two posts. Children shriek as they chase a runaway chicken beneath the creaking wheels of slow-moving wagons.

Outside the bustle, a rugged procession moves along the winding trail south—heavy-duty ore wagons, each groaning under the weight of two tons of raw rock. Ten-mule teams strain against their harnesses, snorting and stumbling as they descend the first steep grade toward Cadiz.

Wheels rattle. Dust billows. One wagon tilts precariously around a tight bend.

MALIKA SMITH (V.O.)

The mine kept giving rock, but the journey to extract the gold was hard and treacherous…

At the crest of the trail, CAMERON SMITH, 66, stands with a leather-bound ledger under his arm, eyes locked on the caravan. His sweat-streaked face is part sunburn, part concern. Beside him, EMMET SMITH, 39, tracks the wagons with a furrowed brow, already calculating weight limits, mule endurance, and the hours to Cadiz. Suddenly—shouts erupt from the line below.

TEAMSTER (O.S.)

Whoa! WHOA! HOLD—DAMN IT—

One wagon’s rear axle splits with a loud CRACK. The iron-reinforced cart jolts sideways, spooking the mules. The lead animals rear up, kicking wildly. The teamster is thrown to the dirt as the cart—loaded with ore—breaks loose.It rockets down the incline—a runaway juggernaut of rock and wood. Miners scramble aside as the cart barrels past, smashing into a boulder at the bottom of the hill with a thunderous impact.

The cart explodes into splinters, ore scattering like cannon shot. One of the mules tumbles over the edge, braying as it disappears out of sight.

Dust settles. Silence follows.

Cameron breathes hard, fists clenched. Emmet is already running toward the trail.

CAMERON

(shouting after him) Check for injuries—get those lines secured before we lose another team!

Below, miners rush to right the overturned cart. One man kneels beside the injured teamster, who clutches a broken arm. Another mule limps away, blood streaking its flank.Emmet reaches the site, barking orders, grabbing ropes, helping reset the line.

Back above, Cameron stares down at the wreckage—his face a mix of rage and fear.

MALIKA SMITH (V.O.)

Every pound of rock came at a price… and the desert always collected her toll.

FADE OUT.

EXT. SOUTHERN PACIFIC RAILROAD OFFICE – SAN FRANCISCO – DAY (1883)

SCREEN OVERLAY: “Two Years Earlier – 1883”

An older, determined Cameron sits across from Collis P. Huntington, president of the Southern Pacific. A large map of the expanding rail network dominates the table.

CAMERON

Sir, a spur from Cadiz to the Barco Mine is a modest investment for a long-term reward.

HUNTINGTON

Mr. Smith, our focus is on connecting major hubs. Your mine is out of the way and offers little return on investment. What guarantees do you offer?

Cameron slides a marked map toward Huntington, pinpointing the Barco Mine in Oasis Palms, and then pushes a ledger detailing the mine’s gold production and estimated reserves. Then Cameron drops a bag of gold nuggets on the map.

CAMERON

A spur to the Barco means 100 tons of gold ore for your trains— and more wealth flowing west every day.

Huntington raises an eyebrow, studying the figures.

HUNTINGTON

Your proposal is intriguing. But our investors don’t gamble on a handshake and a sack of gold. We need hard numbers and certainty.

Cameron leans in.

CAMERON

Lay the track, and I’ll guarantee the freight. You won’t regret it.

Huntington looks Cameron in the eye and presents a sly smile.

HUNTINGTON

Or perhaps you should just sell me your land? You could keep the mine.

Cameron’s frustration is palpable as he packs up his documents. He exchanges a steely look with Emmet as they leave. Cameron turns back and calls-out Huntingtons scheme.

CAMERON

Damn you Huntington, you tried to steal my land 25 years ago. It didn’t work then, it’s not going to work now. I know as well as you do. If I sell you my land, you’ll never build a spur to my mine, you’ll just steal our water and leave us high and dry.

HUNTINGTON

Don’t forget Smith we have a binding agreement that I can build a gravity-fed pipeline from your springs, right down your hill to fill our water tower in Cadiz.

CAMERON

I agreed to supply you with water for your stop in Cadiz. I’ll hold up my end of the bargain, but you need to build my spur.

EXT. BARCO PLATEAU – OASIS PALMS, CALIFORNIA – DAY (1885)

The high desert sun casts golden light across the Barco Plateau. Towering California Fan Palms sway gently, their age-old trunks thick with time. The air is sweet with the scent of Chuparosa blooms, their crimson tubes alive with darting hummingbirds.Below, a modest town square has been cleared from the desert scrub. Simple wooden booths display local goods—dried meats, woven blankets, hand-panned gold flakes. Banners flap in the breeze, one reading: “OASIS PALMS, CALIFORNIA. EST. 1885.”

A gathering of townsfolk—miners, traders, ranchers, mothers with sunburnt cheeks—form a semi-circle beneath the palms. Hopeful eyes mix with furrowed brows. On a raised wooden platform, EMMET SMITH, 40, upright in a clean linen shirt and weathered boots, addresses the crowd.

EMMET

(voice strong and clear) Friends and neighbors, today we mark a new chapter. The Barco Plateau is now officially the town of Oasis Palms, California.

Muted applause ripples through the crowd. Relief glimmers on some faces, but others glance toward the distant mountains, worried.

TOWNSPERSON #1

(whispering) But what about the mine? Everyone knows if that mine goes bust, this town will cease to exist.

TOWNSPERSON #2

(quietly) Production is slowing. My family wagered everything on this place…

Emmet raises his hand, steady and calm. His voice holds the practiced weight of a man used to leading but never forgetting he was once led.

EMMET

I understand your concerns. But look around you. Life is blooming in the desert—because we dared to plant something here.

He gestures outward, to the sunlit palms and flowering shrubs, to the children playing in the dust and the elders watching with wary eyes.

EMMET (CONT’D)

Our future isn’t measured solely in gold—it lies in our resilience, in our grit, and in our willingness to change.

A moment of quiet. Then, the crowd parts slightly as CAMERON SMITH, 68, weathered and upright despite a slight stoop, walks slowly toward the platform. His eyes still burn with fire, but his hand trembles slightly as he grips the edge for balance. At his side, MALIKA, serene and strong, offers quiet support. Cameron interrupts Emmet.

CAMERON

There’s still gold in that mountain. I’ve seen it, felt it in my bones. But what’s more—there’s strength in us. We’ll blast that ore free, haul it down with sweat and steel… and that damn railroad at the bottom of the hill will move that ore, like it or not.

Cameron’s breath catches. He coughs, harsh and dry, but stands tall again. Emmet instinctively steps beside him, steadying without stealing the moment.

EMMET

We honor what brought us here—but we don’t stay chained to it. This land has a spirit. And so do we.

He turns, facing the people—some now nodding, others still wary.

EMMET (CONT’D)

Today, we have named this town Oasis Palms. Let it remind us that even in hardship, beauty and strength take root. We walk forward—together—into a future we will carve with our own hands.

FADE OUT.

EXT. CADIZ RAILROAD DEPOT – LATE AFTERNOON (1885)

A vast, sun-blasted desert plain shimmers with heat. The brand-new Cadiz water tower looms over the siding, casting a long shadow. The word “CADIZ” is painted in bold black letters that glint in the light like a promise—or a warning.Near the tracks, laborers unload heavy wagons of ore by hand, sweat-soaked and sunburned, muscles trembling with effort. Planks groan under shifting weight. Picks scrape metal. Wagons clatter, and train cars—branded with the faded insignia of the Southern Pacific Railroad—creak as tons of raw ore are loaded in.

CAMERON SMITH, 68, rides in slowly on horseback, face stern, shoulders stiff. He dismounts with visible effort. Moments later, EMMET SMITH, 41, arrives on foot, boots dusty, shirt clinging to his back.

They both spot a crew at the center of the chaos—led by an older man with a thick mustache, sharp eyes, and an unmistakable limp. JUAN GARCÍA, 68, Cameron’s longtime friend and the mine’s trusted foreman, is barking orders with the force of a man half his age.

JUAN

Watch the edge! That ore’s heavier than your damn ego, Esteban—lift with your legs, not your back!

Workers laugh. Emmet grins, walking over, wiping his face with a rag.

EMMET

Still running the crew like a cavalry charge, Juan?

JUAN

And you still show up after the hard work’s done, like a general for the victory parade.

They shake hands, strong grip between old friends. Cameron joins them, smiling faintly.

CAMERON

You’re still uglier than I remember, Garcia.

JUAN

And you’re still alive—so I must be doing something right.

Laughter breaks the tension. Then—a loud SNAP cuts through the air. All heads turn. One of the ore wagons tilts sharply—its support plank has cracked. The rear gate, not properly secured, groans. Juan turns instinctively toward it, waving.

JUAN

NO—NO—STOP! THE LOCK PIN—!

Too late. The wagon bed flips open with a thunderous CRASH. A violent avalanche of ore spills out like a tidal wave. Workers leap back—but Juan doesn’t make it. He’s swallowed whole beneath two tons of jagged rock. Dust clouds rise. Screams echo. The world stands still.

EMMET

JUAN!

Emmet rushes forward. He drops to his knees at the edge of the collapse, clawing at the rock with bare hands. Others rush in—shovels fly, men dig desperately.Cameron stands frozen, staring, his face slack with horror. After agonizing seconds, they uncover a hand—lifeless. Then Juan’s crushed body. Silence.

WORKER

He’s gone…

Emmet drops back on his heels, dust and blood on his hands. He stares down, jaw tight, chest heaving.

CAMERON

(quietly, to himself) I brought him here… Forty years in the dirt… and this is how it ends?

The men gather around, hats off, heads bowed. A desert wind stirs the dust, as if nature itself offers a moment of mourning.

EMMET

We can’t keep doing it this way. It’s too slow. Too costly.

CAMERON

Then we will fight for it, son. Before someone else dies for our dream.

EMMET

We need Huntington to build that spur line up to the mine.

CAMERON

That old bastard won’t budge. Railroads won’t spend a dime unless we make it worth their while.

Cameron surveys the chaotic labor—men tossing rock like it’s gravel, train cars groaning under the weight.

CAMERON (CONT.)

Then we’ll give them a reason they can’t ignore. We’ll cut off their water.

FADE OUT.

EXT. OASIS PALMS – NIGHT (1885)

On the porch of their home, an aging Cameron sits, gazing out over the town. The wind rustles through the palm fronds. Malika sits close, sensing the weight of unspoken worries.

MALIKA

Did you tell Isabel?

CAMERON

Of course, they are family. I told her we would take care of her and we will bury Juan with Wilbur and…

MALIKA

You’ve done all you can, Cameron. The town is strong—its people believe in it.

CAMERON

We’ve fought for everything, Malika. But I’m afraid I won’t be here to fight the next battle. I’m tired.

MALIKA

Cameron, you lost your best friend today. Get some sleep tomorrow is a new day.

INT. SMITH HOME – NIGHT (1885)

In a dimly lit bedroom, a frail Cameron lies in bed as a lamp flickers nearby. Malika remains at his side, while their two surviving sons—Emmet, 40, and Jackson, 38—along with their families, gather in quiet farewell.

CAMERON

We built a home and a town. But for our legacy to endure, that railroad must come. If they say no, you must do whatever it takes to convince them.

Cameron closes his eyes; his breath fades as he quietly slips away.

EXT. OASIS PALMS – DAWN (1885)

The town awakens to somber news—Cameron Smith has passed away in his sleep. Malika and Emmet stand at the entrance to their home as townsfolk gather in silent mourning.

INT. EMMET SMITH HOME – NIGHT (1885)

Emmet and his wife Susan Harding Smith discuss the future of the Barco mine with their two young sons CURTIS 9 years old, and JACK 7 years old playing on the living room floor.

SUSAN

Emmet you need to go to Huntington and convince him to build the spur.

EMMET

Huntington just wants the land, he will not settle for anything less.

SUSAN

Emmet you’ve got to go. You’ve got to try.

EMMET

My dad had another idea, it’s risky but it might give us some leverage.

MALIKA (V.O.)

The iron horses came to the desert and their thirst for water would be our only hope for salvation.

EXT. RAILROAD CAMP, CADIZ – 1885 – DUSK

Emmet rides out with a group of trusted men. They arrive at the construction site where railroad workers are settling in for the night. He spots a water tank car on makeshift siding. Emmet dismounts to approach the SITE MANAGER.

EMMET

Can you get a message to Huntington?

The manager nods toward a tent. Inside, Huntington sits at a makeshift desk, poring over maps.

HUNTINGTON

(with a smirk) I figured I’d be seeing you again. I’m sorry to hear about your father, Mr. Smith.

EMMET

You may not care about our ore, but I have something more valuable to you than gold.

Emmet places a map on the table, marking the location of a natural spring that feeds Oasis Palms.

EMMET (CONT’D)

You’ve been after our land for 30 years because of the water. Build the spur to Oasis Palms, and I’ll guarantee your steam trains will have all the water they need when crossing the Mojave.

Huntington studies the map, then leans back, contemplating the strategic value of a stable water supply in the desert.

HUNTINGTON

I had an agreement with your father we are building a pipeline to fill our tower and there’s nothing you can do to stop it.

EMMET

I’ve read the agreement. You can build your pipeline but there is nothing stopping me from charging you whatever I want for the water. Now if you build our spur, I’ll give you all the water you want.

HUNTINGTON

I’m telling you son like I told your father, Southern Pacific has no interest in building that spur. The cost of climbing your mountain with track far outweighs the value of your water.

EXT. VASSAR COLLEGE – 1864 (FLASHBACK)

A sunny afternoon on campus. SUSAN HARDING, vibrant and curious, sits with her sister, FRANCES HARDING, beneath a flowering tree.

FRANCES

So, who’s the cute boy from Yale you met at the dance last week?

SUSAN

(Laughing softly) Oh, you mean Emmet? It was nothing serious—just a dance.

FRANCES

(Grinning) He strikes me as a good prospect.

SUSAN

I heard he’s from California… and his parents are in the mining business.

FRANCES

(Playfully wistful) You know, if I weren’t already seeing Edward back home, I’d snatch him up in a heartbeat.

SUSAN

(With a conspiratorial smile) That E.P. is destined for greatness. You might want to hold on to him. As for Emmet, I might see him again.

EXT. OASIS HARDWARE STORE – MORNING (1885)

A dusty storefront under a painted sign: “OASIS HARDWARE & SUPPLY CO.” Inside, SCOOTER STEPHENSON, early 20s, dusty clothes and sly grin, lays a coiled 100-foot copper line on the counter.

STORE CLERK

That’s a lot of copper for a man who don’t fix pipes. Is that for the mine?

SCOOTER

Nope personal. Not fixin’. More like… creating opportunities.

He winks and drops a few coins on the counter. The clerk watches him go, shaking his head.

EXT. CADIZ RAIL YARD – NIGHT (1885)

Rusting train cars. Stacks of discarded boilers. In the shadows, SCOOTER and ANDREW THOMPSON, mid-20s and quiet by nature, sort through scrap with lantern light.

ANDREW

That busted condenser off the Number 12? She’ll do nicely once we clean her out.

Watchman

Not sure what kind of stove you’re building, but I don’t want no rock-gut. I’m going to need a bottle of the good stuff for that hardware.

SCOOTER

Only the finest for our friends at the Southern Pacific.

They shake hands and agree to trade a bottle of whiskey for the parts. He tips his hat back, smiles, and walks away.

EXT. CADIZ – COAL DEPOT – NIGHT

A single lantern burns as a railroad worker tosses a heavy canvas bag to Scooter.

RAILROAD EMPLOYEE

That’s thirty pounds of coal. Don’t ask me for more till you have that bottle you promised.

SCOOTER

We’re just heating the cave… you know… in theory.

Scooter disappears into the shadows with the bag slung over his shoulder.

INT. OASIS MARKET – DAY

Bags of rye grain are dropped behind the counter. Andrew signs for them under the name “F. Leavenworth.”

MARKET CLERK

Y’all openin’ a bakery?

ANDREW

Sure are. Just a… slow-rising kind.

He smiles flatly, picks up the grain, and leaves.

INT. BARCO CAVES – NIGHT

Torchlight flickers. The still hums with steam and fire. Copper coils gleam in the shadows. Condensation drips into a jug. Andrew and Scooter watch it like proud fathers.

SCOOTER

There she is… born from steam and sin.

ANDREW

White lightning, baby. God bless frontier chemistry.

They each take a swig—then immediately cough and grimace.

INT. BARCO CAVES – AGING ROOM – LATER

Andrew stands beside a rain barrel, now split open. He fires the inside with a torch until it blackens. Smoke curls up into the cave ceiling.

ANDREW

Charred oak. Same as Kentucky. Just don’t tell Kentucky.

They fill the first aging barrel with their raw spirit. The sound echoes softly through the cave. Around them: cool air, 80% humidity, and silence.

SCOOTER

Ten years from now, someone’s gonna say this place makes the best whiskey in the West.

ANDREW

Yeah… assuming no one dies drinkin’ it until then.

FADE OUT.

INT. AT&SF HEADQUARTERS – CHICAGO – BOARDROOM – MORNING (1886)

SCREEN OVERLAY: “AT&SF Headquarters – Chicago, 1886”

A long, polished mahogany table dominates the boardroom. Above it, a sprawling map of the western United States is riddled with red pins—routes claimed, territories conquered. But California remains a blank expanse, pierced only by a few SP lines like blood veins in desert sand. Executives in waistcoats murmur behind coffee cups. The clock ticks like distant rail joints.

E.P. RIPLEY, early 40s, poised and precise, is seated with a small group of executives. CHARLES MORRISON, senior executive with silver hair and a gravel-lined voice is seated at the head of the table. Morrison pushes forward a sealed leather folder.

MORRISON

Gentlemen, we need to crack California. We need a direct line into Los Angeles—freight, passenger, all of it. Huntington’s got the politicians in his pocket, and Southern Pacific blocks us at every turn. What have you got for me?

Ripley opens the folder. Inside—survey maps, freight logs, route schematics—all centered on the Southern Pacific corridor from Barstow to Los Angeles. One town is circled twice: Cadiz.

RIPLEY

Sir, technically, Santa Fe still can’t operate in California. But the Atlantic & Pacific Railroad can. If we secure controlling interest in the A&P, they have legal right-of-way on Southern Pacific’s track.

MORRISON

Interesting. They are ripe for the taking I could push an A&P deal through by the end of the quarter.

Morrison and Ripley scan the maps as they cook-up their plan. His brow furrows slightly at a name pinned near Cadiz—Barco Plateau. Ripley points at the map.

RIPLEY

That’s Mojave country. My brother-in-law, Emmet Smith, just inherited a mining operation there. He’s building a small town just south of the mainline. Close to Cadiz.

MORRISON

Even better. After I close the deal, you’ll go west—as an A&P inspector. Uniform, papers, the whole bit. Quietly assess the route on the leased line from Barstow. Look for weaknesses. A soft spot we can pry open.

RIPLEY

And if Southern Pacific gets wind of it?

MORRISON

Then you’re just a railman checking his lines. Nothing more.

ANOTHER EXECUTIVE

But between us—we want that corridor. It’s the keystone. Not just a lease, if we get control of that line into Los Angeles Huntington will choke on his own arrogance.

Ripley closes the folder slowly. A glint of mischief and steel flickers in his eye.

RIPLEY

Then I’ll take a walk through the desert… and see what I can stir up.

FADE OUT.

INT. BARCO CAVES – NIGHT

Deep inside the cave, past the mine shafts, the still hisses like a sleeping beast. Copper coils gleam in the torchlight. A second vertical pipe—rigged from scavenged brass and iron—rises beside the main still like a crude tower. A new condenser, hammered into shape from train scraps, drips crystal-clear distillate into a jug.

ANDREW

Second column’s in. That’ll clean the spirit another pass. We’re gonna polish this thing like a gold coin.

SCOOTER

Double-distilled, desert-aged… We might be damn geniuses.

Scooter dumps the first half-gallon of the run into a rusty tin pail. It steams on contact with the stone floor.

SCOOTER

Toss the heads. That’s the ghost that blinds a man.

ANDREW

You want the run that smells like sweet rye and fire.

They lift the next jug beneath the spout. The clean, middle cut of the run begins to drip steadily. Andrew opens a burlap sack and pulls out a bundle of dried wood chips—blackened, aromatic.

ANDREW

Mesquite and charred oak. It’s like a bonfire made peace with a bottle.

He drops a handful into a ceramic jug and pours in the fresh shine. The spirit turns golden almost instantly.

SCOOTER

Now… we cut it.

They lift a leather bucket from the cave spring—clear, ice-cold water untouched by time. Scooter measures and pours.

SCOOTER

Thirty percent Barco spring water. Ten-thousand-year-old glacier piss.

ANDREW

Fancy folks would pay a fortune for that phrase alone.

They swirl, pour, and raise tin cups. Sip. A pause. Then—nods. Satisfaction. No coughing. No wincing. Just a slow, creeping grin on both faces.

SCOOTER

Hot damn. That ain’t lightning. That’s a gold vein in a bottle.

EXT. BEHIND THE SALOON – NIGHT

Scooter and Andrew rummage through a pile of empty bottles behind the saloon. They pull out thick, dark-colored glass bottles—some with faded fancy labels, others just dusty and solid. They clink the bottles together like stolen treasure.

ANDREW

High-end and half-forgotten. Sounds like us.

They carry the bottles back toward the cave entrance, moonlight spilling across the desert floor.

FADE OUT.

EXT. SOUTHERN PACIFIC MAINLINE – CADIZ, CALIFORNIA – DAY (1887)

The desert sun beats down on a scene of industry and tension. Southern Pacific railcars stand in a long line at the Cadiz siding, their black paint baking under the Mojave sun.A crew of workers in Atlantic & Pacific uniforms walk the rails, measuring clearances, inspecting bolts, and taking notes. Among them: E.P. RIPLEY, his coat dusty but his posture sharp, quietly observing every detail.

Nearby, heavy ore carts are being offloaded by Emmet’s men. The ore is shoveled into Southern Pacific freight cars with tired rhythm and little joy.

In the distance, a rider kicks up a trail of dust—EMMET SMITH, late 30s, lean, sunburnt, arrives on horseback. He reins in beside the tracks and dismounts. Emmet notices the A&P logos on the workers uniforms.

EMMET

Edward. I got your wire, but I thought you were with Santa Fe?

RIPLEY

We own ’em. Just keeping it quiet for now.

They shake hands—firm, like men who trust each other but can’t afford to say it out loud.

RIPLEY

SP’s got this place locked up tighter than a mine shaft in a cave-in. But the cracks are there. You still own that patch of land east of the plataue?

EMMET

Ten acres, it’s the road our mules use to get the ore off the hill. We have a pipeline there that feeds this water stop. Huntington’s been trying to buy it since Pa was alive.

RIPLEY

Don’t sell. Not ever. That land’s the key. The water is your leverage.

EMMET

What are you thinking?

RIPLEY

How about we build a private spur? Quiet. Not on SP’s ledger. Tie it into the A&P alignment just north of here. You keep the ore flowing, but ship it on our equipment.

I can’t get the spur to the mine, but I can get it to the top of the hill. It’ll cut your wagon trips down 90% and we’ll cut Southern Pacific out completely. We can do business together.

EMMET

SP owns the mainline. We’ll get sued before we get the second tie laid.

RIPLEY

Only if they find out. For now, you stockpile. Divert just enough ore to look like a bottleneck. Blame the rail schedule. Let it build. Then we move fast—rails laid in a week, cars rolling before the ink dries.

EMMET

And what about the water? They’re using my spring to run the tower.

RIPLEY

Cut it. Quietly. Redirect it to the new spur siding. You’ve got rights. Let ‘em haul water from Needles if they want it.

Emmet glances at the SP workers nearby, still oblivious. A sly smile creeps into the corner of his mouth.

EMMET

So we choke ‘em out slow… then ship everything under their noses.

RIPLEY

Exactly. By the time they realize what’s happening, it’ll be too late.

The wind picks up, whistling low between the rails. Emmet looks out at the desert—toward the distant plateau where Barco rises like a promise waiting to be claimed.

EMMET

Alright. Let’s stir up some ghosts.

FADE OUT.

INT. BACK ROOM – CANTEEN SALOON – OASIS PALMS – NIGHT (1886)

The saloon bustles outside—piano music, clinking glasses, drunken laughter—but in the back room, it’s quieter. Shadows stretch across a cluttered storeroom stacked with cheap whiskey crates, cracked chairs, and broken barstools. SCOOTER and ANDREW sit at a table with a single bottle of their homemade spirit between them—dark glass, no label, a red wax seal dripping down the neck. Across from them, DIXON, the saloon owner, mid-50s, bald with a suspicious squint, swirls a glass of their shine with a poker player’s skepticism.

DIXON

You two boys selling snake oil or kerosene? ‘Cause if this melts my guts, I’ll take it outta your hides.

SCOOTER

Ain’t neither. Try it.

Dixon sniffs the spirit—lifts an eyebrow.Then sips.

He waits, lips pursed… swallows. Another pause. Then another sip—larger this time.

DIXON

…Damn.

Scooter smirks. Andrew leans forward, elbows on the table.

ANDREW

That’s Barco Rye Whiskey. Cut with glacial water, polished twice, and kissed by mesquite.

DIXON

You boys poets now, too?

SCOOTER

Just drunks with ambition.

Dixon sets the glass down, eyes the bottle.

DIXON

You got more of this?

ANDREW

Maybe. Depends who’s askin’… and what he’s paying.

Dixon smiles—a slow, greedy thing.

DIXON

You sell it to me in crates—no questions, no names—I’ll pay triple what I give the distributors. But if I hear a whisper about you two selling it out the back of someone else’s place? You’ll find yourselves at the bottom of the well in the caves.

Scooter and Andrew exchange a glance. A beat. Then Scooter reaches into his satchel and sets down a second bottle.

SCOOTER

We can deliver one case every two weeks. Call it… “the private stock.”

DIXON

Private. Right. Get outta here before I sober up and change my mind.

The boys nod, grab their satchel, and slip out through the back door—vanishing into the desert night.

FADE OUT.

INT. SOUTHERN PACIFIC OFFICES – SAN FRANCISCO – EXECUTIVE SUITE – DAY (1890)

SCREEN OVERLAY: “4-years later 1890”

Tall windows overlook the Bay, but the mood inside is anything but calm. COLLIS P. HUNTINGTON, now in his late 60s, paces behind a massive desk stacked with ledgers and telegrams. His gold watch chain glints as he turns. Across from him, a nervous RAILROAD ACCOUNTANT flips through freight receipts and quarterly returns.

HUNTINGTON

What do you mean we’re losing money on the Mojave line? We’ve run ore out of Barco for a decade. Did that mine finally go bust?

ACCOUNTANT

Sir… the Barco shipments didn’t stop. They’ve been increasing. But… they’re not moving on our lines.

HUNTINGTON

(eyes narrowing) Then whose are they moving on?

ACCOUNTANT

Atlantic & Pacific. Built a private spur three years ago. It connects just east of Cadiz. We didn’t catch it because they laid it on privately held land. No permit filings until after the line was operational.

Huntington’s face flushes. He turns to the window, fists clenched behind his back.

HUNTINGTON

So they’re draining our freight, using our water rights, and funneling profit eastward while we sit here staring at empty ledgers.

ACCOUNTANT

It gets worse. They’ve petitioned for expansion rights to run a new passenger corridor from Barstow to Los Angeles—through Mojave. If it’s approved—

HUNTINGTON

(gritting his teeth)—then they’ll own the goddamn desert.

EXT. OASIS PALMS – OUTSKIRTS – DAY (1890)

The midday sun scorches the hard-packed earth, but the town of Oasis Palms is alive with motion. A freshly painted railcar with a big No5 painted on the side, sits on a siding just beyond the town’s edge, workers loading ore with practiced rhythm. The Santa Fe logo gleams faintly on the metal. Dust swirls as mules strain and carts groan. Shouted orders echo over the desert floor.Closer to town, SCOOTER and ANDREW guide a wooden wagon loaded with dark glass bottles toward the saloon. The cases are clean, sealed, and unlabeled — but the smell of something stronger than promise hangs in the air.

INT. SALOON – FRONT ROOM – CONTINUOUS

The saloon owner, DIXON, wipes sweat from his brow as Scooter and Andrew enter through the front door — a new touch of legitimacy to their once-shadowed dealings.

DIXON

You boys finally learned to knock?

SCOOTER

Figure if the train’s running legal… we oughta start lookin’ the part too.

Dixon grins and takes a case, prying open the lid to reveal six wax-sealed bottles nestled in straw.

DIXON

Still callin’ it Barco Lightning?

ANDREW

No. This batch is cave-aged 4-years, mesquite smoked, and cut with glacier water. That’s frontier rye whiskey now.

DIXON

You should get some labels, come up with a catchy name.

They all laugh as Dixon stacks the cases behind the bar. Outside, a train whistle echoes through the desert — low and long.

EXT. SALOON PORCH – MOMENTS LATER

Scooter and Andrew lean against the post, watching the ore train ease forward on the spur. Dust rises behind it like a curtain.

ANDREW

You think one day they’ll be loading whiskey barrels instead of ore?

SCOOTER

We got near twenty barrels aging back in that cave. In two-three years, they’ll be ready. That’s sipping whiskey — the real deal.

ANDREW

All we need’s a label… and a permit.

Scooter nods his head and looks at the Santa Fe box car.

SCOOTER

(chuckling) We should call it Old No.5. But the label’s gonna be easier than the permit.

They watch the train in the shimmering heat, the sun dipping low on the horizon. A new day for Oasis Palms is coming — one railcar, and maybe one bottle, at a time.

FADE OUT.

INT. AT&SF HEADQUARTERS – CHICAGO – BOARDROOM – DAY (1890)

A brass plaque is being mounted beside the office door: E.P. RIPLEY – GENERAL MANAGER. Inside, the same polished boardroom. Ripley, now sharper, more commanding, stands before a map with bold new lines drawn west of Barstow—connecting directly to Los Angeles. Around the table, Santa Fe executives nod approvingly as reports are handed around.

EXECUTIVE #1

The last shipment out of Barco ran straight to San Pedro. On our rails. Not a penny to Southern Pacific.

EXECUTIVE #2

The spur cut ‘em off. But it’s the water rights that sealed it. Emmet Smith registered a new tower site at Danby under an A&P shell company. SP can’t refill west of Needles without paying our toll.

RIPLEY

And the politicians?

EXECUTIVE #1

We backed two in Sacramento and one in Washington. The Mojave Corridor bill will pass. We’ll have federal right-of-way by fall.

Ripley walks to the map, taps a red line connecting Barstow to Los Angeles. A corridor Southern Pacific once claimed as unbreakable.

RIPLEY

Gentlemen, the Mojave is ours.

FADE OUT.

EXT. CADIZ WATER STOP – MOJAVE DESERT – DAY (NOVEMBER 27, 1892)

SCREEN OVERLAY: “Two Years later 1892”

A vast, golden desert stretches beneath a cloudless sky. The rails shimmer in the distance as a plume of steam cuts across the Mojave horizon. At the Cadiz water tower, polished and freshly painted, a small group waits in anticipation. Among them, EMMET SMITH, now 48, dressed in his finest wool coat and hat, and SUSAN HARDING SMITH, elegant in a long blue dress with white gloves, stand hand-in-hand.

A whistle splits the dry air. With a hiss of brakes and a proud groan of steel, the Santa Fe California Limited rolls into the whistle-stop station—glimmering like a black arrow in the sun. Steam vents. The desert falls silent in reverence.

From one of the forward cars, E.P. RIPLEY, now a senior executive with the weight of empire in his posture, steps down onto the platform. Beside him, his wife, FRANCES HARDING RIPLEY, radiant in travel attire, smiles warmly.

FRANCES

Susan! You haven’t aged a day. Tell me, are the boys still driving your house wild?

SUSAN

Every waking minute Curtis is headed to college and Jack is so sweet, he’s my baby boy. And your girls, how are they?

FRANCES

They have both grown into beautiful young woman. E.P. tries to manage them like the railroad, but they pull his strings at every turn.

The two women laugh, falling into easy conversation as they stroll a few steps toward the water tower. Ripley and Emmet remain near the train, watching the engine crew fill the tender from the tower using the spring-fed line Emmet once fought to protect.

EMMET

She’s a fine train, Rip. Never thought I’d see the day steam from Chicago would roll into Cadiz.

RIPLEY

Neither did I, it’s the final stitch in the Santa Fe quilt. It’s what you and I set into motion six years ago. How are things up on the hill?

EMMET

Oasis Palms is growing. We’ve got clean streets, a Hotel, and a piano that almost stays in tune. You need to run the spur all the way into town and put a little station there. Your passengers could get out and stretch their legs and see a piece of the Mojave they will never forget. And if you run the line to the mouth of the mine, we could move a lot more ore on your rails.

RIPLEY

(smirking) I like the idea. Hell, I’d ride it myself. But Manvel’s in charge now. I don’t have that kind of pull…

RIPLEY (CONT’D)

…yet.

They share a knowing glance. The conductor calls out, “All aboard!”

EMMET

Congratulations on the California Limited, keep us in mind Oasis Palms has a lot to offer.

Clara hugs Susan goodbye. Ripley tips his hat to Emmet. The California Limited pulls away in a symphony of steam and steel, leaving behind the promise of something more.

FADE OUT.

INT. BARCO MINE OFFICE – OASIS PALMS – DAY (1894)

SCREEN OVERLAY: “Two Years later 1894”

A sturdy wooden desk sits beneath a dusty window, papers and ledgers stacked in orderly chaos. Maps of the plateau, rail routes, and geological surveys cover the walls. EMMET SMITH, now 50, rubs his temples as he pores over ore projections and rail tariffs. The mine office creaks in the wind. The door opens quietly. SUSAN SMITH, graceful, composed, steps in holding a yellow Western Union envelope.

SUSAN

Telegram just came through. From Frances.

Emmet looks up as she hands him the Telegram. He reads it, then leans back in his chair.

EMMET

“E.P. has been promoted to President of the Santa Fe.” Huh.

SUSAN

That’s good news, isn’t it?

EMMET

Sure is. But he’s got a job ahead of him. I heard Manvel almost bankrupted the whole damn company.

SUSAN

Honey, you know better than most, old-industrial money never really goes away. It just… moves around.

SUSAN (CONT’D)

And anyway, the Santa Fe is too big to fail.

Emmet chuckles, sets the telegram on the desk, and stares out the window at the desert. A wagon rattles past outside, the dust golden in the afternoon light.

SUSAN

You should go visit E.P. See if he’ll finish the spur. Having a station up here — a proper one — would turn this into a real town.

EMMET

(half-grinning) You think a platform and a roof’ll turn us respectable?

SUSAN

No, it’ll bring people. And money. The hotel could grow from a boarding house into something proper. The train has been hauling away our gold. If we had a station, it could bring some in.

Emmet smiles, thoughtful. He glances again at the telegram.

EMMET

Alright. I’ll go see the man in the big chair.

FADE OUT.

EXT. AT&SF HEADQUARTERS – CHICAGO – DAY (1895)

A backdrop of smoke, steel, and ambition. The clamor of the industrial city hums behind the limestone walls of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe headquarters. Inside a spacious executive office cluttered with survey maps, freight manifests, and engineering blueprints, EMMET SMITH stands across from E.P. RIPLEY, now president of the railroad. Ripley looks older—distinguished, confident, with a faint weariness in his eyes—but his handshake is still iron-strong.

EMMET

E.P., good to see you. How are Frances and the girls?

RIPLEY

(chuckling) Lively as ever. But let’s not pretend you came all this way just to ride my train and swap family news.

EMMET

(smirking, straightening) Fair enough. I’ve seen more passenger trains coming through the Mojave—steam burns hot, and you and I both know: more engines means more water.

EMMET (CONT’D)

You need water. We need to move ore. You finish the spur from Cadiz into Oasis Palms, right up to the mine, and I’ll guarantee the Santa Fe all the water it needs in the Mojave.

RIPLEY

(slowly, with amusement) Are you mining diamonds up there now, Emmet? Because you’ve got the time and pressure part down pat—you sure don’t quit.

Ripley smiles, then leans back, nodding to himself. There’s a beat—then a decision.

RIPLEY

Alright. For the sake of steam, steel—and Susan—I’ll do it. You helped me beat Huntington, I’ll finish the spur and build you your station. I’ll send a survey crew next month to map the route.

Emmet allows himself the smallest of smiles. He doesn’t thank Ripley—because he knows the fight’s only half over.

MALIKA (V.O.)

The ties that bound our families—and our water—became the lever for change. The future of Oasis Palms now rested on steel rails.

FADE OUT.

EXT. OASIS PALMS – 1896 – DAY

SCREEN OVERLAY: “One Year Later – 1896”

The town bustles with activity. Santa Fe railroad crews lay track across the scrubby desert edge of Oasis Palms, iron rails gleaming in the sun. Engineers and surveyors huddle over blueprints, hands on hips, eyes on the plateau.

On the edge of the mine’s ridge, a narrow shelf of land drops sharply into rock-strewn canyon. A temporary siding is already being framed going into the caves and right up to the entrance of the mine for ore loading. But space is tight, the terrain stubborn.

MALIKA SMITH (V.O.)

The iron road had arrived, but the land would not yield. The plateau was too small, the mountains too steep…

EMMET SMITH stands with SCOOTER at his side, both watching as a SANTA FE SURVEYOR, young but weary, waves his arms in frustration and folds a creased map.

SURVEYOR

We can lay a siding here to load the ore cars, but no way a passenger train can get in and turn around. Not without backing out all the way to Cadiz. The ridge is boxed in.

EMMET

We need passengers, we need a station. I promised Susan she could board a train right there that’ll take her to Los Angeles to visit Jack in college.

SCOOTER

Unless…

He spits into the dust and gestures toward the side of the canyon behind them—toward the old caves tucked behind the mine.

SCOOTER (CONT’D)

You blast through that limestone wall, just past my spring-water operation—we’ll come out of the caves on the other side of town.

SURVEYOR

You mean just past the spring-water “aging barrels”? There’s solid rock between here and there.

SCOOTER

Mostly. But it’s not granite. That cave’s been hollowin’ itself out for a thousand years. We push through, you’ll have a straight line past Main Street. Trains could roll in, turn, and leave the same way they came.

The surveyor raises an eyebrow and looks at Emmet.

SURVEYOR

This man always talk like an outlaw engineer?

EMMET

Only when he’s right.

The surveyor marks something on his chart, thinking it through.

SURVEYOR

We’d need explosives. Controlled teams. Structural support on both sides.

SCOOTER

Well lucky for you… I’ve got a rock man, and a whole town full of folks who like to blow things up.

Emmet looks out across the bustling town, where rail meets rock and the desert air carries the scent of iron, dust, and something like possibility.

EMMET

Let’s make a hole and give this town a railroad station.

FADE OUT.

MATCH CUT TO: EXT. CAVE TUNNEL CONSTRUCTION SITE NEAR MINE ENTRANCE – NIGHT

The darkness is thick, broken only by flickering lanterns casting eerie shadows on damp rock walls. The rhythmic CLANG of pickaxes echoes through the cavern as WORKERS chip away at stone, their faces slick with sweat, their bodies aching from relentless toil.

EMMET, grips a lantern, inspecting the work. SCOOTER, a seasoned foreman with a grizzled beard watches as ANDREW, wiry, with nervous energy, drills into the rock with a hand auger. The cavern feels too still. A distant rumble slithers through the stone like a growl from the deep. A worker named JONESY pauses, his breath hitching.

JONESY

(uneasy, to himself) Did you feel that?

SCOOTER

(Frantic) Drew, are your boys blasting in the mine today?

ANDREW

Damn it! I told them to wait for me.

BOOM! The walls shudder violently as an explosion rips through the rock. A horrific, low groan echoes through the cavern as tons of rock give way. Dust and debris erupt like a volcanic blast.

WORKER

Cave-in, in the mine!

Panic. The mine entrance behind them shakes, fractures, and then collapses. Workers scream, diving for cover. Torches flicker wildly. Shadows stretch and twist across the walls as men scramble to escape. Some aren’t fast enough. A sickening CRUNCH of rock slamming down. The desperate SCREAMS of the trapped turn muffled under tons of rubble.

SCOOTER

(Frantic) Get the ropes! We have to dig them out!

Emmet grabs a coil of rope and tosses one end to a worker. They run to the mine and their hands shake as they dig, pry, and pull. A worker unearths a lifeless arm beneath a boulder. Another finds a crushed leg, boot still on. The living are dragged from the wreckage, coughing blood, gasping for air.

MATCH CUT TO:EXT. CAVE ENTRANCE – DAY

A WORKER stumbles forward out of the cave and into the daylight, blood seeping from his scalp other beleaguered workers follow. His eyes flicker upward. Through the haze of dust and lantern light, he sees it—a TRAIN. A work train sits at the end of the unfinished track, waiting. The engine looms like a specter, a monstrous black hulk with its iron wheels silent, its smokestack exhaling a thin stream, as if impatient for the tunnel to be cleared. The workers freeze, staring at it.

Some see opportunity—a train means progress, more ore, wealth. Others see doom—an unstoppable force devouring the mountain, swallowing their mine whole.

WORKER

(softly, shaken) Damn train is going to kill us. It’s just waiting.

WORKER #2

(grim, wiping dust from his face) Progress ain’t stoppin’ for us.

MATCH CUT TO: EXT. CAVE TUNNEL CONSTRUCTION SITE NEAR MINE ENTRANCE – NIGHT

The flickering lantern light catches gold dust in the rubble, scattered like dying embers. The mine’s riches—its future—might soon be buried beneath steel and rails. The weight of this realization settles over Scooter and Emmet as the train’s headlamp flares brighter into the cave, piercing the dust like an all-seeing eye.

MALIKA (V.O.)

Men have always tried to bend the desert to their will. The desert always has the last word.

FADE TO BLACK.

EXT. OASIS PALMS – DAY (1898)

SUPERIMPOSE: “Two Years Later – 1898”

A steam locomotive, elegant and gleaming, winds its way through the desert, chuffing past the town cemetery — where weathered headstones mark the final resting places of the Warrior, the Smiths, and Barco miners lost to the mountain.

The train descends into Oasis Palms, whistling triumphantly. It slows beside a crisp white Santa Fe station, where bold black letters declare: “OASIS PALMS.”

Passengers disembark in formal dress, shading their eyes to gaze at the towering fan palms of the nearby oasis, swaying in the wind like sentinels of the past.

FADE TO BLACK.

FADE IN:

The conductor’s voice cuts through the stillness:

CONDUCTOR (O.S.)

All aboard!

The locomotive shudders to life, hissing and rumbling forward. It rolls toward the mouth of the mountain, entering the newly completed Oasis Palms Tunnel — smoke billowing up through vents into the jagged cliffs above, silhouetted by the lookout at Cliff Hanger Point.

MATCH CUT TO:

EXT. CAVE NEAR MINE ENTRANCE – DAY

The train glides through the dark tunnel. Passengers crowd the windows in awe as torchlight flickers on the rock walls. Outside, Barco miners push ore carts along a newly completed wooden trestle and pause to watch the train pass, faces coated in dust and wonder.

MATCH CUT TO:

EXT. CAVE EXIT – DAY

The nose of the locomotive bursts into sunlight. The train emerges into town again — now from the far side — rolling slowly across Main Street as shopkeepers and townsfolk look on, shading their eyes.The train climbs the outer ridge, wheels hammering the rails, before curving out of view and disappearing into the golden horizon.

MALIKA SMITH (V.O.)

Once a foe, the railroad became a savior. For a season, the mine’s renewed wealth flowed. But as quickly as the train arrived… the gold would disappear.

FADE TO BLACK.

INT. BARCO MINE OFFICE – DAY

SCREEN OVERLAY: “2 Years Later 1900”

A late afternoon haze spills through the grimy window of the Barco Mine office. Dust motes drift in the fading light. Ledgers sit open but untouched. A cracked map of the mountain hangs crooked on the wall — streaked with pencil marks and old hopes. EMMET SMITH stands at the desk, fists clenched, staring at production reports that tell the same story in every column. SCOOTER leans in the doorway, his shirt soaked with sweat, face streaked with dust and resignation.

SCOOTER

(shaking his head, weary but firm) Sorry Emmet, we’ve chased every vein to the edge of the mountain. There’s nothing left but dust and fools’ luck.

EMMET

There’s got to be more. Maybe deeper—another shaft—

SCOOTER

You can keep hauling rock to Berdo if it makes you feel better. But there’s no gold in them anymore. Hell, it costs more to move the stuff than it’s worth.

SCOOTER (CONT’D)

We can go the other way, toward town… open a new drift. But that’ll put us under the springs.

A beat. Emmet’s eyes lift slowly to the wall map. His gaze settles on the small blue circle labeled OASIS SPRING, then back to the faint lines of caverns curling beneath it. He says nothing, but the tension sets in his jaw. One wrong blast… and the town’s water could vanish forever.

SCOOTER (CONT’D)

The truth is… the only thing these caves still reliably produce is my grandpap’s whiskey.

A long silence. Emmet lowers himself into the old desk chair. It creaks beneath the weight of failure and memory. His eyes drift toward the ledger — and then toward the framed survey of the rail spur… and the caves beyond. Outside, the wind stirs the plateau. The whistle of an approaching train echoes faintly in the distance. Will he risk the springs?

MALIKA SMITH (V.O.)

The mountain gave us its riches — then swallowed the rest. But buried in the dark, something else was waiting.

FADE TO BLACK.