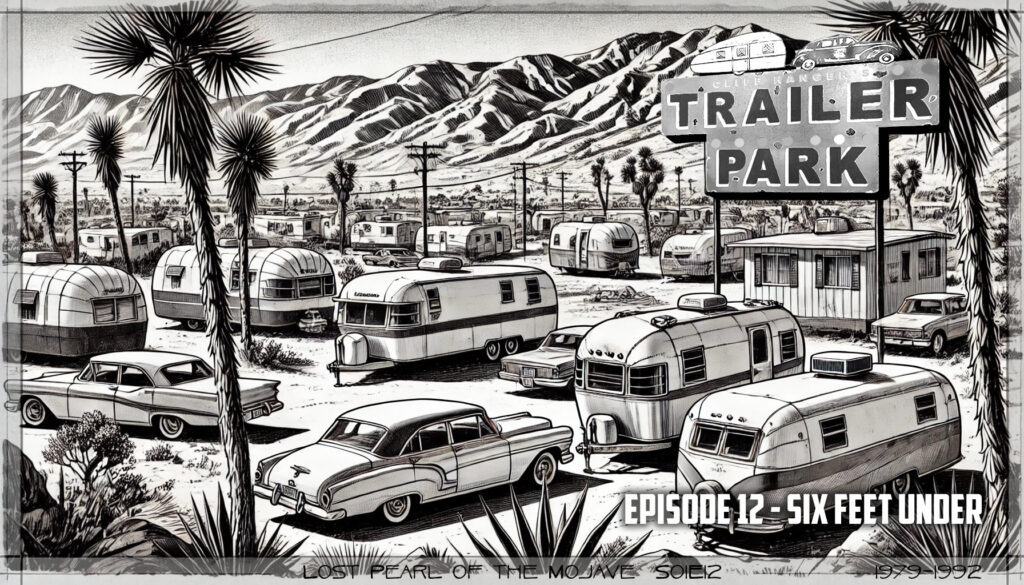

The Lost Pearl of the Mojave – Episode 12: Six Feet Under

The Lost Pearl of the Mojave – Episode 12

Six Feet Under 1979-1992

Six Feet Under 1979-1992

INT. FLOYD’S TRAILER – DAWN (1979)

FLOYD is startled awake, his heart pounding. The whole trailer is shaking violently. Empty bottles rattle across the floor. A flickering lamp crashes onto the nightstand. A used heroin kit scatters to the floor. Beside him, a strung-out girl stirs but doesn’t wake. She mutters incoherently, lost in some drug-induced haze. Then—a deep, guttural groan of metal. A sound that doesn’t belong. A sudden, thunderous crash shakes the air. The walls of the trailer shudder. Distant screams cut through the morning.

EXT. CLIFF HANGER TRAILER PARK – DAWN – CONTINUOUS (1979)

FLOYD stumbles outside, barefoot, barely able to keep his balance as the ground beneath him ripples and jerks. Parked cars rock violently. A propane tank tips over, leaking gas. Across the lot, other junkies spill out of trailers, wide-eyed and panicked, some falling to their knees as the aftershocks ripple through the earth. Then, another sound. A deafening metallic groan. Twisting. Snapping. Collapsing.

EXT. CLIFF HANGER LOOKOUT – DAWN – MOMENTS LATER (1979)

FLOYD crosses the road and reaches the edge of the overlook, where the desert drops off into the town below. He grips a street sign to steady himself, panting, eyes darting. Below him, Oasis Palms is in chaos. The elevated railroad structure has failed. A massive section of the tracks has collapsed, the heavy metal beams crushing the back of the Pool Hall, Hotel California, and Scooter’s Saloon. A cloud of dust and debris rises into the air. Suddenly its early quiet and a vulture circles in the sky.

As FLOYD watches, frozen. The walls of the Pool Hall begin to crack. The barber pole falls off the wall, Then, with a sickening groan, the roof caves in. A few figures jump from the Hotel California’s balcony, barely escaping as the building shifts, its foundation crumbling beneath it. Another explosive crash—Scooter’s Saloon tilts forward, its entire front facade crumbling into the street. FLOYD’s breath catches. His town is imploding in front of him.

Then one by one the last remaining support beams of the railroad structure creak, then snap. The theater, hardware store, and market are all damaged as their bricks crumble and fall in sheets. The final section collapses, sending another wave of destruction rippling through downtown and then the train station roof collapses. The entire town shudders, then stills. Smoke. Silence. The once-bustling town of Oasis Palms is reduced to ruins. FLOYD stares, numb. The dream had already died. Now, the town itself has followed.

INT. HOTEL CALIFORNIA PENTHOUSE – NIGHT (1978)

SCREEN OVERLAY: “One Year Ago 1978”

LEFTY lies in his old bedroom, now a shell of what it once was. The place is dusty, unkempt, the furniture draped in sheets. A bottle of heart medication sits untouched on the nightstand. Out the tall windows, in the distance, a dust devil is forming on the desert floor. FLOYD stands at the foot of the bed, high as hell, swaying slightly. His father’s labored breathing fills the room.

LEFTY

(weakly) Look at yourself…

FLOYD sniffs, wiping his nose, avoiding his father’s gaze.

LEFTY

(barely a whisper) This town… you had a chance…

Lefty’s breath catches. He exhales—long and slow. Lefty takes his last breath, then stillness. Lefty is gone. FLOYD doesn’t move. He stares at his father’s lifeless form, his bloodshot eyes vacant.

INT. HOTEL CALIFORNIA LOBBY – DAY – FUNERAL AFTERMATH (1978)

The funeral is over. What’s left of Oasis Palms’ old guard has come and gone. The lobby is silent, filled only with the scent of stale cigarettes and faded memories. JIM OVERMAN, dressed in his only suit, with his red hat in hand, stands near the front doors, a duffel bag slung over his shoulder. He watches as FLOYD sits at the bar with a bottle of Rye, drinking alone, his tie undone, his suit wrinkled.

JIM

(softly) I’m done, FLOYD.

FLOYD doesn’t look up. Just raises his glass.

FLOYD

(flat) Cheers.

Jim lingers for a moment. Then shakes his head, lays his red ball cap on the bar, turns, and walks out. Through the glass doors, we see him toss his bag into his prize possession ’69 Camaro Pace Car Convertible, starts the engine, and pulls away. FLOYD, still at the bar, pours himself another drink. The glass trembles in his hand.

EXT. OASIS PALMS – DAY (1980)

Floyd wanders through the streets of the dead town. The streets, once lined with brick buildings and tourists, are now empty and silent. Every remaining building is boarded up, most of them still in ruins from the earthquake. The pool hall is a husk, its roof collapsed in on itself. The Hotel California’s facade is cracked, its windows gaping holes of shattered glass. Only the old theater marquee remains standing, the letters “NOW SHOWING CALIGULA Malcolm McDowell The Lust. The Power. The Madness of Rome. X-RATED – NO ONE UNDER 18 ADMITTED” fallen away. On the hill the Flamingo Motel stands but the neon sign has fallen from the roof.

EXT. CLIFF HANGER TRAILER PARK – DAY

FLOYD stands next to his father’s old beat-up pick-up, its faded red paint peeling under the desert sun. His old Airstream trailer is hitched to the back, weighed down by years of neglect. The last remnants of life in Oasis Palms are scattered in the dirt—a toppled shell lawn chair, a rusted-out cooler, a forgotten pair of boots baking in the heat.

The engine of the truck coughs to life. FLOYD puts the truck in gear, the trailer lurching forward behind him. Floyd drives down the hill past the boarded-up motel turns the corner and drives past his father’s Mobil station, the P-38 laying on the ground with one wing crashed through the window of his father’s office.

EXT. ATOMIC JACKALOPE – DAY (1980)

SCREEN OVERLAY: “One Year Later 1980”

As Floyd drives slowly past, the lone resident, UNCLE BILL, 60 years old, a weathered man in a cowboy hat, stands near the road in front of his trailer. The home-made Atomic Jackalope sign laying in the front yard next to his old VW Bus. Floyd stops as Bill walks up to the passenger window.

UNCLE BILL

So that’s it, huh? You’re out?

FLOYD

(without looking up) Yeah.

UNCLE BILL

(gesturing to the ruins) You ever think about rebuildin’? With the insurance money?

FLOYD stops. For a second, he just stands there, then lets out a small, bitter laugh.

FLOYD

(shaking his head) What insurance?

UNCLE BILL

(confused) The town must’ve had something, right? Your folks had plenty of dough.

FLOYD tightens his grip on the wheel.

FLOYD

Policies lapsed.

UNCLE BILL

(frowning) And the government, what about them? Won’t they help?

FLOYD

(flat) The government wasn’t gonna lift a damn finger. McDonnell saw to that.

The wind howls through the street. The weight of it all hangs heavy in the air.

UNCLE BILL

(softly) So what now?

FLOYD glances toward the highway, his future as barren and uncertain as the desert beyond.

FLOYD

(with a smirk) Nyland near the Salton Sea. I got a buddy down there who wants me to help him build a mountain.

FLOYD laughing

FLOYD

They say nobody gives a damn what you do out there.

FLOYD puts the truck in gear, and inches away. The last remaining resident watches as FLOYD’s car disappears down the cracked road, kicking up dust that hangs over Oasis Palms like a final ghost.

FADE TO BLACK.

EXT. MOJAVE DESERT – DAY – MONTAGE (1980)

The sun hangs low and white in a hazy sky as FLOYD, gaunt and wired, grips the steering wheel of a beat-up red 1950s Chevrolet tow truck. Behind him, an aluminum Airstream rattles over cracked blacktop.

RUSTED TOOLBOXES clang in the truck bed. A cassette tape whines out classic rock through fried speakers. Floyd lights a cigarette with trembling hands.

- The truck passes the faded remains of Roy’s Motel and Café in Amboy—boarded-up, its neon sign unlit, its Motel vacant. A ghost of Route 66, still standing.

- The adobe walls of the Joshua Tree Inn rise from the sand like an old prayer. A broken vending machine hums faintly. Room 8 sits in silence, its porch light flickering, a faded wreath of plastic flowers nailed to the doorframe. One flickering “VACANCY” sign clings to the front office. Floyd doesn’t stop—just looks, then drives on.

- The Salton Sea glimmers on the horizon. He slows as he passes the North Shore Yacht Club, once a shining desert escape. Now it’s abandoned, its dock stranded far from the receded shoreline. The earth is dry, crusted with white salt. A plastic lawn chair sits askew in the dust. He coughs into his fist. Wipes sweat from his brow. Drives on.

- Then—color. At the edge of the desolate flats, a sudden splash of brilliance: a painted Salvation Mountain of adobe and straw, screaming with reds, blues, pinks, and greens. At its center: bold white letters—“GOD IS LOVE”. Beneath the sign, LEONARD, paint-splattered and sunburned, stands on a ladder. He looks up and nods his head as Floyd passes. No words. Just recognition.

- Floyd turns left. Gravel crunches under his tires as he enters Slab City. The Airstream weaves through rows of squatters, RVs, art shacks, and sunburnt eccentrics. Dogs bark. A fire barrel smokes. Wind chimes rattle in the dry wind. He pulls into an empty space at the far end of a row. Kills the engine. Silence.

Floyd leans back in his seat. Stares at the sunburned horizon. The last cigarette burns to his fingers. He doesn’t flinch.

MALIKA (V.O.)

The road ends where the world forgets to keep going. But some people… some people find peace there.

EXT. SALVATION MOUNTAIN – SUNSET (1980)

Paint peels and glows under the dying sun. “GOD IS LOVE” towers over the desert floor in kaleidoscopic layers of adobe and latex paint. LEONARD, wiry and sunburned, stands barefoot on a ladder, brush in hand.

Below, the Chevy tow truck rattles to a stop. FLOYD climbs out slowly. Hollow eyes. Yellowed fingertips. He looks like he hasn’t eaten or slept in days.

Leonard sees him. His face breaks into a tired but genuine smile.

LEONARD

Well I’ll be damned. Floyd Smith. (beat) I haven’t seen you since the protests at the VA clinic in LA. (grins) You still hanging out with rock stars?

Floyd squints up through the sunlight. Smiles faintly.

FLOYD

The stars are hiding up in the hills. Still out here painting the desert, huh?

LEONARD

Still tryin’. Saw you drive by with your trailer the other day. Gotta say you—look like hell.

Floyd laughs dryly, lights a cigarette with a shaking hand.

FLOYD

I’m fine. (poetically) I mean I’ve seen hell, but Hell’s just a dry heat, an empty bottle, and a broken mirror.

LEONARD

You always were a bad poet.

Leonard climbs down from the ladder and walks over, eyeing Floyd with gentle concern.

LEONARD

I could use a hand. Paint’s drying faster than I can lay it. Honest work helps clear the head.

Floyd hesitates. His cigarette burns down, ash fluttering to the ground. He won’t meet Leonard’s eyes.

FLOYD

My heads fine, I’m just here to shake the ghosts.

LEONARD

Then you came to the right place. (disarming smile) Out here we embrace the ghosts.

Floyd stares at the mountain—at the paint, the prayers, the mess of it all. His fingers twitch. Something stirs, but he says nothing. Leonard turns back toward the ladder. Picks up a brush. Without looking back—

LEONARD

I got extra brushes if you want one.

FLOYD

Maybe tomorrow.

Floyd stands there, smoke curling around his face. A breeze kicks up, flapping the hem of a painted banner nailed to the adobe.

FADE OUT.

EXT. SALVATION MOUNTAIN – MONTAGE – WeEKS (1980)

Time passes. The sun rises and sets in wide desert skies. Wind howls, then calms. The mountain grows.

- FLOYD and LEONARD paint side by side—balancing on ladders, mixing paint in old buckets, laying down stripes of bold color across cracked adobe. Their conversations are quiet but steady.

- At night, they sit by a small campfire. Floyd smokes less. His hands are steadier. Laughter, once rare, now comes easy.

- In the mornings, Floyd wakes inside the Airstream. At first it’s a mess—empty bottles, ashtrays, clothes everywhere. Slowly, things change.

- He makes his bed. Opens the windows. Sweeps the dust out the door.

- One morning, he stands in front of the small kitchen sink, staring at the last bottle of Barco Rye. He uncaps it, smells it… then slowly, deliberately, pours it down the drain.

Outside, the wind shifts. The desert exhales.

EXT. SALVATION MOUNTAIN – SUNSET – LATER (1981)

SCREEN OVERLAY: “One Year Later 1981”

The sky burns orange behind the mountain. Leonard and Floyd stand at the base, paint-stained and sunbaked, watching the colors dry on a new section of wall.

LEONARD

You’ve come a long way, friend. I’m proud of you.

Floyd doesn’t respond right away. He squints at the mountain—then turns to Leonard, eyes clear for the first time in years.

FLOYD

I appreciate that. (beat) But I’ve got to go… and work on my mountain. (softly) It needs salvation.

Leonard just nods. No sadness. No surprise. Only understanding.

LEONARD

Just remember, the things you do for others are more important than the things you do for yourself. If you have the time they still need plenty of help

Floyd turns toward the setting sun, the desert stretching out before him—vast, broken, and full of possibility.

FADE OUT.

EXT. OASIS PALMS – WELCOME ARCH – DAY (1981)

Dust kicks up as the red Chevy tow truck rolls past the rusted sign: “WELCOME TO OASIS PALMS”. The letters are faded, tagged with graffiti.

Floyd cuts the engine. The Airstream creaks behind him as it settles. He steps out, older, steadier. Clear-eyed for the first time in years. A shotgun clicks behind him.

UNCLE BILL (O.S.)

That better not be another looter.

Floyd turns slowly. UNCLE BILL, mid-60s, dusty and wiry, stands on the porch with a double-barrel shotgun resting in his arms. He squints… then his face softens.

UNCLE BILL

Well I’ll be damned. (beat) Floyd Smith. You look… almost human.

FLOYD

Been working on it.

UNCLE BILL

Thank God you’re back. I’ve been holdin’ this place together with spit and birdshot. Looters come by weekly now. Taggers, tweakers, goddamn scavengers. I think some of them used to be your friends.

Floyd surveys the wreckage—graffiti on the saloon walls, shattered windows at the motel, collapsed porch of the theater. The bones of Oasis Palms still stand, but they’re brittle. Tired.

FLOYD

She’s worse than I remember.

UNCLE BILL

She’s barely standing. So am I.

FLOYD

Yeah… one step at a time. (beat) First, admit it’s a mess. Then start picking up the pieces—one nail, one board, one brick. That’s how you build anything worth saving.

Uncle Bill studies him for a long moment, then lowers the shotgun.

UNCLE BILL

You sound like someone who’s been through something.

FLOYD

Been through hell. Found my way back with a paintbrush and a broom.

UNCLE BILL

This place is going to need more than a paintbrush and a broom.

FLOYD

Maybe my mom’s place can get this clean-up kick-started. I’ll see if I can find a buyer for the diner.

Bill turns his head and looks down the street. The HotRod Diner, although boarded up and graffitied, was the only structure not severely damaged by the earthquake.

FADE OUT.

EXT. OASIS PALMS – HOTROD DINER LOT – DAY (1982)

SCREEN OVERLAY: “One Year Later 1982”

The sun beats down as a flatbed tractor-trailer idles in a cloud of diesel smoke. Cranes and loaders carefully lower the chrome shell of the old HotROd Diner onto the truck bed, one gleaming panel at a time.

The diner is disassembled but still beautiful—its turquoise tiles cracked, neon letters faded, but the bones are there. A piece of another time.

Nearby, a MAN IN SUNGLASSES, late 30s, casually dressed but clearly well-funded, counts out a thick stack of cash and hands it to FLOYD.

FLOYD

Where you taking her?

MAN

Los Angeles. (grinning) Gonna polish her up real nice and drop her on Melrose. Retro brunch crowd’ll eat it up.

Floyd looks back at the skeleton of Oasis Palms. The graffiti. The cracked windows. The ghosts.

FLOYD

She was my Mom’s pride and joy. I grew up eating eggs and bacon there almost every morning.

The man doesn’t hear—or doesn’t care. He’s already directing his crew. Floyd pockets the cash. Stands in the dust as the flatbed pulls away, chrome reflecting the desert sun like a farewell wave.

FADE OUT.

EXT. SALVATION MOUNTAIN – EARLY EVENING (1983)

SCREEN OVERLAY “1 Year Later 1983”

FLOYD’s beat-up red pickup tow truck, with a rattletrap flatbed trailer, piled high with scrap metal—bound for the scrap-yard in Indio, pulls off the dusty road.

On his trip he parks beside the painted slope of Salvation Mountain, the late sun casting long shadows over the colorful adobe. Leonard sits cross-legged on an overturned bucket, carefully dabbing blue paint onto a faded heart.

Floyd climbs out of the truck with a slight wince, thermos of coffee in hand, and leans against the fender. He watches Leonard work as the sky slowly darkens to violet and gold.

FLOYD

Figured I’d check on you before cashin’ in my treasure haul at the scrap-yard in Indio. (scratches his chin) You ever think of painting a dollar sign on this place and charging admission?

LEONARD

Just hearts and heaven, brother. That’s all I got room for.

They share a quiet smile as the desert wind stirs. Then Leonard dips his brush again, and the conversation settles into something deeper…

LEONARD

You know… I’m proud of you, but staying clean is not just about what you don’t do. It’s about what you do with your hands now.

FLOYD

Like painting mountains?

LEONARD

Sure. Or building ‘em. Or helping someone who’s still crawling outta their hole.

Floyd sips the coffee, considering. His hands tremble slightly but he doesn’t try to hide it.

LEONARD

There’s a VFW hall down in Palm Springs. Bunch of old guys set up an outreach post—nothing fancy. Some donated food, bad coffee, a busted fan that never stops squeaking. Maybe you could help.

FLOYD

You volunteering me?

LEONARD

I’m suggesting. Big difference. (beat) They could use a steady hand. Someone who’s been through it—not some clipboard caseworker.

FLOYD

I don’t know if I’m ready, Len.

LEONARD

Maybe not. But you’re standing. And that’s more than most.

Floyd looks off at the horizon. The painted words “GOD IS LOVE” catch the last light.

FLOYD

Palm Springs, huh? (beat) Been a while I was pretty high last time I was there. Guess I could see what kind of coffee they’re serving.

LEONARD

It ain’t good. But the company’s honest.

They sit in silence as the wind picks up. No judgment. Just forward.

FADE OUT.

EXT. OASIS PALMS – ELEVATED RAIL WRECKAGE – LATE AFTERNOON (1983)

The sound of the flatbed truck fades in the distance. Dust settles. Floyd stands still for a moment, then turns and walks with purpose toward a nearby construction crew taking a break.

A twisted section of the old elevated rail loop lies collapsed across the desert floor—warped steel from the quake years before.

Floyd approaches the CREW CHIEF, a sun-leathered man in a hard hat sipping from a thermos. The workers glance over, unsure what to expect.

FLOYD

How many machines did you bring?

CREW CHIEF

Three loaders, two dozers, and a crane.

Floyd points toward the twisted rail.

FLOYD

That loop used to carry tourists all the way to the chapel and back. (beat) I want it cleared. Hauled out. You keep can scrap the steel, I need to see the oasis again.

The crew chief eyes him, unsure—until Floyd reaches into his coat and starts peeling off crisp stacks of cash, one after another.

CREW CHIEF

Cash jobs, huh?

FLOYD

Only kind that works out here.

The chief looks at the cash, then at the rail wreckage—then nods.

CREW CHIEF

We’ll start at first light.

Floyd nods. He doesn’t smile, but something lifts in him. A shift. One splintered piece of Oasis Palms at a time.

FADE OUT.

EXT. OLD HOTROD DINER LOT – DAWN (1984)

SCREEN OVERLAY: “One Year Later 1984”

A thin light creeps over the broken sign where the diner used to stand. Weeds push through cracks in the concrete. The Airstream sits parked on concrete foundation, surrounded by rusting tools and half-empty paint cans.

INT. AIRSTREAM – CONTINUOUS (1984)

FLOYD, late 30s, lies in his narrow bed, tangled in a sweat-damp sheet. His face is pale. His T-shirt clings to his chest. He coughs softly—then harder. He sits up, dizzy. A hand to his forehead. Eyes unfocused. He’s drenched in sweat, like he’d run a mile in his sleep.

He stands. Legs wobble. He grips the edge of the small kitchen counter to steady himself. Opens a cabinet. No aspirin. Just a chipped mug and a half-bag of oats. At the sink, he splashes water on his face. Looks in the cracked mirror. His reflection stares back: eyes sunken, cheeks drawn, skin just slightly off-color. Like something underneath is starting to show.

FLOYD

Just the flu. Just the damn desert.

But he knows it’s not. He opens the Airstream door, letting in the sharp morning light and desert air. He squints out toward the wide, empty town. Everything is quiet—too quiet. A single bird lands on a power line above. A sign of life. Or maybe a witness.

Floyd steps outside. Lights a cigarette. His hands tremble as he brings it to his lips. But he lights it anyway. He looks toward the diner’s old footprint—just a concrete pad now. But in his eyes: a flicker of fight. He’s not done yet.

FADE OUT.

EXT. FLAMINGO MOTEL – MID-MORNING (1984)

The Flamingo Motel stands boarded up under the desert sun. Its pink stucco is cracked and faded, old neon sign is missing. Windows are busted, graffiti covers the doors, and the once-proud sign out at the street is full of rusted bullet holes.

In the lot, FLOYD and UNCLE BILL haul mid-century furniture—vinyl chairs, atomic lamps, a cracked Formica dresser—onto a creaky rattletrap flatbed trailer hitched behind Floyd’s red pickup.

Sweat pours off them. Dust swirls with every step. Floyd works with steady urgency, sleeves rolled up, face focused. Uncle Bill grunts as he lifts a box of mismatched drawer handles.

UNCLE BILL

I don’t know, Floyd. (grimaces) My back’s not what it used to be, and this place… this place might already be gone.

FLOYD

I need to keep going. If I can just salvage one building… just one, then its a first step.

UNCLE BILL

A few chairs ain’t going to rebuild those red-tagged brick buildings in town.

FLOYD

I get it. (beat) But they will pay me a pretty penny for these in Palm Springs. I appreciate your help.

Uncle Bill stops, wiping his brow with a faded bandana. He looks at Floyd—sees the clarity in his eyes, the steadiness in his hands.

UNCLE BILL

I’ll lend a hand to you, whenever, where ever I can. But This place holds a lot of ghosts.

FLOYD

So do I. (shrugs) But I’ve learned to embrace my ghosts.

They lift an old motel nightstand together and slide it onto the trailer. The legs creak, but it holds. A wind kicks up, rustling a sun-bleached motel curtain still clinging to the second floor.

FADE OUT.

INT. PALM SPRINGS DESIGN GALLERY – LATE MORNING (1985)

SCREEN OVERLAY: “One Year Later 1985”

Air conditioning hums over a curated silence. A sleek Palm Springs gallery gleams with polished concrete floors and desert light. Mid-century chairs, lamps, and artwork are arranged like sculpture. Everything is expensive—on purpose.

FLOYD, sweat-stained but steady, stands next to a pair of vinyl side chairs and a turquoise bedside tables. The GALLERY OWNER, early 40s, sharp-eyed and casually flawless, circles the furniture like a hawk.

GALLERY OWNER

Oh my! What have you got for me this time? More atomic desert chic, people eat this stuff up in L.A. As always, I’ll take it all.

FLOYD

I’ve got more buried in the desert. I’ll keep digging for you.

The gallery owner nods, impressed. He hands Floyd an envelope of cash. As Floyd reaches out, the gallery owner notices a faint purplish spot on Floyd’s forearm.

GALLERY OWNER

Oh honey, I don’t want to pry but do you do a lot of work in the sun?

FLOYD

Yeah. Why?

The owner reaches behind the counter and scribbles something on a business card.

GALLERY OWNER

Could be nothing. Could be sun damage. But… you should have that checked. (handing him the card) That clinic’s discreet and good. Ask for Dr. Carmen.

Floyd looks at the card. Doesn’t say anything. Just nods and tucks it into his shirt pocket.

EXT. PALM SPRINGS – VFW POST – EARLY AFTERNOON (1985)

After dropping off a fresh load of Vintage Furniture to the gallery, Floyd’s red pickup idles in the dusty lot outside a small, faded VFW hall. A hand-painted sign on a building in the back reads: “VETERANS OUTREACH KITCHEN – SAT/SUN MORNINGS”. Inside, the smell of burnt coffee and bleach drifts through the open doors. JANINE the kitchen manager in an apron sets out plastic bins of canned goods.

INT. VFW KITCHEN – MOMENTS LATER (1985)

Floyd stands at the folding table, filling out a volunteer form. His hands are steady. His name at the top: FLOYD SMITH.

JANINE

You got any kitchen experience?

FLOYD

My Mom owner a Diner. I know how to serve a hot plate and wash dishes, that good enough?

JANINE

That’s all we need. Can you be here on the weekends?

Floyd looks around the room. A few older vets sit quietly at folding tables, some in worn caps, some just staring at the wall. It’s quiet—but not empty.

FLOYD

(nods) These days I’m making weekly scrap runs from my place just above Joshua Tree, I’ll be here, you can count on me.

He pockets a volunteer badge and steps outside, the desert sun hitting his face. He squints into the light.

FADE OUT.

EXT. FLAMINGO MOTEL – DRY POOL – DUSK (1986)

SCREEN OVERLAY: “One Year Later 1986”

The Flamingo Motel stands behind them—freshly painted white, its doors bright in primary colors Orange, Yellow, Blue. A string of working bulbs flickers to life along the roofline as the sun slips behind the mountains.

In the bottom of the dry swimming pool, FLOYD and UNCLE BILL sit in folding lawn chairs, the cracked tiles beneath them swept clean. A deep fracture in the floor has been patched with concrete.

Uncle Bill holds a cold beer, the bottle sweating in the heat. Floyd sips from a glass bottle of Coke, his sleeves rolled up, hands stained with brightly colored paint.

UNCLE BILL

You think this thing’ll hold water again?

FLOYD

We’ll see soon enough. Biggest problem’s McDonnell down in Cadiz.

UNCLE BILL

McDonnell? Hell, I haven’t heard that bastard’s name in a while. Thought it was quiet down there.

FLOYD

Not anymore. McDonnell sold his Cadiz property to some investment banker from England. Word is NASA ran a satellite over the Mojave—turns out we’re sitting on the largest untapped body of fresh water in Southern California.

UNCLE BILL

Satellites, huh? Aliens been flyin’ over this desert for centuries. How do you think that Lost Pearl Boat got dropped here?

FLOYD

(laughs) You still telling those old stories?

UNCLE BILL

You wouldn’t be here if your great-grandpappy didn’t believe ’em.

FLOYD

Technically, great-great-grandfather. (pause) But who’s counting?

They stare up at the stars, each taking a quiet sip—wondering what the heavens will give them next.

UNCLE BILL

Y’know… Lately, I’ve been feeling like a car that outlived its last oil change. Still runs. But the engine knows its about done.

Floyd glances at him. Doesn’t speak right away. Just nods.

FLOYD

When everyone else left… you stuck around. Didn’t try to fix me. Just kept the wolves at bay.

Bill shrugs. Takes a long pull from his beer. Looks to the deepening dusk.

UNCLE BILL

A man’s gotta have something to believe in. For me, I guess… it was you.

Floyd swallows hard. Looks out across the quiet motel lot—still rough, still unfinished, but no longer abandoned.

FLOYD

You were the first thing I saw when I came back. Maybe you’re the reason I stayed.

A warm wind stirs the broken diving board above them. A lone cricket begins its slow, rhythmic song in the corner of the pool. Uncle Bill leans back, eyes closed, a peaceful half-smile on his face.

Floyd watches him for a long beat. Then turns his gaze skyward—the stars just beginning to scatter across the desert sky, like old souls finding their way home.

Floyd and Uncle Bill shared their last drink that night and Floyd buried him in the graveyard behind the ruins of the old church, like he was a member of the family.

FADE OUT.

INT. VA OUTREACH KITCHEN – PALM SPRINGS – EARLY MORNING (1986)

The VA outreach kitchen hums with quiet activity. A few older veterans sit at folding tables with paper plates of scrambled eggs and toast. A radio crackles in the background, playing a slow FM oldie from 1972.

FLOYD, wearing an apron over a sun-faded shirt, works behind the serving counter. He ladles out eggs with practiced care, nodding to each vet who passes through.

A tall, thin man with tired eyes steps forward. His jacket is frayed, his boots worn down, but his back is still straight. Name tag reads: FRED JENKINS.

FRED

You Floyd Smith?

FLOYD

That’s me. (handing over a plate) You hungry?

FRED

Always. (beat) I think I knew your brother. Lloyd. We served together—Phu Bai, back in ’68. He was a hell of a guy.

Floyd’s hands pause mid-motion. He looks up, eyes searching Fred’s face for something familiar.

FLOYD

He never talked much about the war. Or anything, really.

FRED

Yep, he was quiet, but solid. Carried more than most. (beat) I heard he made it home only to go out in a blaze of glory up on ’66 near Needles.

Floyd hands Fred a cup of coffee. There’s a long beat of silence between them. He notices Fred’s dirty clothes and duffle bag.

FLOYD

That was a lifetime ago, but I miss him. (beat) Are you doing ok? You got a place to sleep tonight?

FRED

Nah. I’ve been bouncing around. VA motel vouchers only go so far. I’ll be ok.

FLOYD

Well… an old friend of mine just moved out. He’s in a better place. (beat) His trailer’s empty. It’s not fancy, but it’s clean. It’s a few miles north of here in the desert, but if you lend me a hand with chores, it’s yours—until you get back on your feet.

Fred looks up, surprised. Unsure how to respond.

FRED

You’re serious?

FLOYD

Dead serious. (pause) Besides, Lloyd is up there too and I think he would like the idea of one of his buddies keeping an eye on me.

Fred chuckles softly, nods once. Takes a sip of the coffee.

FRED

Then I guess I’m hired.

They share a quiet moment behind the counter, the clatter of plates and slow hum of the radio wrapping around them like a warm wind.

FADE OUT.

EXT. OASIS PALMS THEATER – LATE AFTERNOON – 1987

SCREEN OVERLAY: “One Year Later 1987”

The desert wind picks up dust along the broken sidewalk. The once-grand Oasis Palms Theater stands half-gutted—its marquee letters long gone, but its bones still full of stories. On a tall ladder in the lobby, FLOYD balances carefully, reaching up to detach a rusted Art Deco light fixture. His clothes hang looser—he’s noticeably thinner. Paler.

FRED stands below, holding tools, keeping a watchful eye. Floyd loosens the final bolt—but his foot slips. In a blur, he loses balance, the fixture tipping— CRASH! The light shatters on the pavement as Floyd hits the ground hard, coughing, trying to catch his breath.

FRED

Floyd! You all right?

FLOYD

I’m fine. My foot just slipped, that’s all.

He tries to stand but his legs tremble. He sways, gripping the side of the ladder for balance. Fred steps forward, steadying him.

FRED

You’re not fine. (beat) I’m taking you to the clinic in Palm Springs tomorrow whether you like it or not.

FLOYD

Fred, really—

FRED

Don’t argue with me, man. You helped me get off the street. Now it’s my turn to help you.

Floyd doesn’t respond right away. He just looks at the shattered glass on the ground, then back at Fred. His pride flickers… but he nods. Fred offers a hand. Floyd takes it. They walk off slowly, past the empty theater doors, as the desert sun dips behind the rooftop and throws their long shadows across the dust.

FADE OUT.

INT. PALM SPRINGS COMMUNITY CLINIC – EXAM ROOM – DAY (1987)

The room is small, whitewashed, and sterile. A wall fan clicks quietly. A faded poster about nutrition peels in the corner. FLOYD sits on the paper-covered exam table, thin arms crossed, eyes on the floor.

Across from him, a calm and practiced DOCTOR—mid-40s, white coat, clipboard in hand—flips through lab results. A long silence. Then, carefully:

DOCTOR

Mr. Smith… the test results came back. (beat) You’ve tested positive for HTLV-III. (softly) That’s what we’re currently calling the virus. It’s what’s causing AIDS.

FLOYD

AIDS? What do you mean, AIDS? (beat) That’s… that’s men in San Francisco. I’m not—

DOCTOR

It can come from a variety of exposures. IV drug use. Blood transfusions. Heterosexual contact with someone who had an infected partner. (beat) The virus doesn’t care who you are. Just how it gets in. We’re just learning more but we think this goes back to the 70’s and can lay dormant for quite a while.

Floyd stares at the floor. His fingers twitch slightly. The silence returns, heavy with implication.

FLOYD

Are you telling me I’m dying? How long do I have?

DOCTOR

There’s no way to know for sure. Some people live with it for years before full symptoms. Others… (beat) We’ll monitor your T-cell counts. What matters now is managing your health, watching for infections.

Floyd finally looks up, his voice low but steady.

FLOYD

There’s no treatment, is there?

DOCTOR

Not yet. Trials are just beginning. But support exists. Counseling. Groups. You don’t have to go through this alone.

Floyd nods faintly. But his eyes are already far away.

FLOYD

I’ve been alone before.

The doctor opens a drawer and pulls out a small, tri-fold flyer. On the front: a simple sunburst logo and the words: “Desert AIDS Project – Support. Care. Hope.”

DOCTOR

They’re local. Confidential. You wouldn’t be alone there.

Floyd takes the flyer slowly. Looks at it for a beat. His thumb brushes the corner. Then he folds it shut, tucks it into his shirt pocket—next to a half-crushed pack of cigarettes. He nods once, curt and quiet.

FLOYD

Thanks, Doc.

He rises from the table, shoulders heavier now. The paper on the exam table crackles as he moves. He opens the door and steps out into the waiting room—where sunlight spills in through dusty glass. Outside, life continues. Floyd stands still for a moment. Then puts on his sunglasses, and walks out into the glare.

FADE OUT.

EXT. SUNSET MOTEL – LATE AFTERNOON (1987)

Fresh paint gleams on the white stucco walls of the Sunset Motel. Doors in vibrant colors catch the golden light. The sign, newly re-lettered by hand, reads: “SUNSET MOTEL – REOPENING NEXT MONTH”

FLOYD and FRED carry a new window A/C unit toward one of the rooms. Floyd moves slower than he used to, but his hands are steady. Fred handles most of the weight, glancing toward the dry swimming pool.

FRED

Still no water?

FLOYD

Nope. Springs are barely a trickle. Could’ve been the quake. (pause) Could be CADIZ sucking the basin dry from under us.

They set the unit down gently and catch their breath. Behind them, a few rooms are made up—simple but clean, each with new linens and a coat of fresh paint.

FRED

Guess we’re not a resort anymore. More like… an honest place to crash.

FLOYD

That’s enough. Basic beds, cold A/C, hot coffee in the morning. It’s more than most people get.

Fred nods. He looks out across the lot, where a couple of lawn chairs sit beneath a shade tarp. A beat-up cooler and a makeshift grill wait nearby. Home, of a kind.

FRED

What’s left on the list?

FLOYD

Just the occupancy permits. County’s dragging their feet. But we’re close.

Fred leans on the doorway, looking out at the horizon.

FRED

When we open, you want me at the front desk or changing sheets?

FLOYD

Both. You’re employee of the month by default.

They laugh. It’s a quiet, easy moment. The wind stirs the tarp, the screen door creaks gently, and somewhere, a distant freight train rumbles past like a memory refusing to leave.

FADE OUT.

EXT. SUNSET MOTEL – EARLY MORNING (1988)

A dusty county pickup truck rolls into the lot, past the faded “REOPENING SOON” banner. The re-named Sunset Motel gleams in fresh white paint and brightly colored doors. A sense of pride hangs in the air. FLOYD stands near the office steps, adjusting his shirt collar. FRED leans against the porch railing, sipping coffee from a thermos.

COUNTY INSPECTOR DAHL, mid-50s, clipboard in hand, steps out of the truck. Buttoned-up but not unfriendly, he eyes the property with cautious professionalism.

DAHL

Morning. Floyd Smith?

FLOYD

That’s me.

DAHL

Dahl. County Building & Safety. Here to do your final inspection for occupancy. (looks around) Place looks a hell of a lot better than it did last year.

Floyd nods with quiet pride. Fred offers a half wave.

FRED

We got A/C in the rooms and hot coffee in the office.

Dahl chuckles, flipping a page on his clipboard.

DAHL

Let’s walk it.

They move from room to room. Dahl checks smoke detectors, tests GFCI outlets in the bathrooms, notes the fire extinguisher placements. He kneels, inspects under sinks, then steps into the mechanical room and peers at the breaker panel.

DAHL

You rewired this yourself?

FLOYD

Mostly. Had a buddy double-check it. Former Navy electrician. Pulled permits for all the work.

DAHL

Looks clean. Marked properly. No mice nests—bonus points.

He scribbles a note and walks outside toward the motel’s structure. He studies the stucco, then raps a knuckle against a foundation support.

DAHL

These exterior walls… they original?

FLOYD

Far as I know. Early ’50s build, solid as a rock.

DAHL

Uh oh. That means unreinforced masonry. (beat) You’ve done good work here. Clean rooms. Plumbing’s solid. But the building code changed after ’79. For full occupancy—especially lodging—we’re going to need seismic anchoring. Slab bolts, bracing at load points. Nothing fancy, but it’s gotta be done.

Floyd’s face tightens slightly. He looks toward Fred, who offers a small nod—no panic, just resolve.

FLOYD

How bad?

DAHL

If you know your way around a hammer drill and a big wrench? You could do most of it yourself. Get it signed off after.

FRED

How long we got?

DAHL

Sixty days before I close the file and you’d have to start all over and reapply. (beat, glancing toward the pool) And one more thing: that empty pool’s not up to code. Fill it with water, or fill it with dirt. Either way—no permit until it’s handled.

He tears off a yellow carbon copy and hands it to Floyd.

DAHL

Fix the bones, Mr. Smith. Everything else is good to go.

INT. DON’S BARBERSHOP – MORNING (1988)

Dust hangs in the air like memory. Sunlight filters through cracks in the boarded-up windows. The barbershop is a time capsule—yellowed linoleum, rusted scissors on the counter, old clippings curled on the wall. Most of it’s been stripped or broken. The roof is caved in and birds are nesting in the rafters.

FLOYD and FRED work together, grunting as they tilt an antique barber chair—red leather torn, chrome dulled—through the doorway and out onto the sidewalk. Outside, the old pickup with flatbed trailer idles on the street.

FRED

Ain’t much left to sell down here. (beat) I really hope we get the motel up and running soon.

FLOYD

We will. (points to the chair) I’ll take this into town—see what I can get for it. Should be enough to pay the skid steer guy.

They load the chair onto the flatbed, strapping it down with sun-faded tie-downs.

FLOYD

Tell him to fill the pool with rubble from the old church—there’s still a whole back wall ready to come down. Then smooth it off with sand. (beat) But make sure he doesn’t disturb the graveyard behind it. Not a single stone.

FRED

Got it. And if he finishes before you get back?

FLOYD

Buy him a Coke and stall him. I’ll be back this afternoon with the cash.

Floyd wipes his brow, swings into the truck. The engine grumbles to life as Fred steps back, watching him roll down the sun-bleached street, leaving a trail of dust behind.

Fred turns back toward the motel, eyes narrowing at the church ruins in the distance—half standing, half collapsed, shadows stretching toward the graveyard.

FADE OUT.

EXT. BEHIND A MODERN ART GALLERY – PALM SPRINGS – MIDDAY (1988)

FLOYD’s flatbed truck is parked behind a sleek, glass-fronted Palm Springs design gallery. The antique barber chair is still strapped down in the bed—faded red leather, flaking chrome, heavy with history.

The GALLERY OWNER, tan, tailored, and wearing designer sunglasses, walks slowly around the chair, arms crossed.

GALLERY OWNER

It’s got charm, I’ll give you that. But this isn’t our kind of stuff, too old. But I know a guy a couple of hours from here in Riverside who might take it.

FLOYD

Riverside?

GALLERY OWNER

Oh yes, he’s got props, movie rentals, all sorts of weird inventory. He works with the Hollywood crowd. They rent and buy all kinds of stuff when they are making movies.

But, Floyd darling, how are you feeling? Did you go visit the clinic?

FLOYD

I’m fine. But I really need to sell this (beat) today.

He scribbles something on the back of a gallery card and hands it to Floyd.

GALLERY OWNER

Ask for Cal. Tell him I sent you.

Floyd looks at the card, then the chair. Then he nods, tosses the last of his Coke bottle in a nearby trash bin, and climbs into the cab of his truck.

FADE TO:

INT. RIVERSIDE WAREHOUSE – LOADING DOCK – LATE AFTERNOON (1988)

The warehouse is massive and chaotic— rows of chandeliers, jukeboxes, church pews, streetlamps, clawfoot tubs— everything dusty, half-labeled, and waiting for its next role in someone’s masterpiece.

FLOYD and the warehouse MANAGER (CAL, 60s, flannel shirt, clipboard) carefully unload the antique barber chair off the flatbed onto a wheeled dolly.

CAL

She’s got good bones, but she needs love. Upholstery’s shot. Chrome’s pitted. Base is frozen. (beat) Sorry this isn’t more money, but we’ve gotta put work in before we can rent it out or flip it.

He counts out some bills—less than Floyd hoped, but more than nothing.

CAL

Now… you ever come across a saloon back bar? Western, late 1800s, tall mirrors, carved columns—real deal, not reproduction.

FLOYD

I might have something.

CAL

Got a client in L.A. collecting stuff for a ranch he wants to build in Santa Barbara. He wants it to be like a theme park. He’s building a western saloon to serve rootbeer to the kids and will pay top dollar for authenticity. You bring me the right piece, and we’re talkin’ four figures, maybe even five for the right piece.

Floyd thinks for a moment. His eyes shift—calculating. He nods once.

FLOYD

I’ll let you know if I find something.

He turns, walking back to his truck as Cal wheels the chair into the shadows of the warehouse. Somewhere, a forklift beeps. Neon buzzes. Dust dances in shafts of light.

FADE OUT.

EXT. SUNSET MOTEL – PARKING LOT – DUSK (1988)

The sun dips low, casting long golden shadows across the cracked concrete. The freshly painted SUNSET MOTEL stands behind them—white stucco glowing, doors in bright colors, windows clean, room numbers hand-stenciled with care. A brand new Costco neon sign mounted above the office buzzes to life with a soft flicker: “OPEN” in red tubing.

FLOYD and FRED stand in the empty parking lot, shoulder to shoulder. Both hold steaming cups of coffee, sleeves rolled up, faces lit by the last orange sliver of sun. No guests. No cars. Just quiet. They look out over what’s left of downtown Oasis Palms—a skeleton of its former self.

Down the hill:

- Five red-tagged brick buildings, windows shattered

- The once-grand theater, now a hollow shell

- A Mobil gas station, long closed, with a rusted-out P-38 fighter plane wedged nose-first into the office

- Floyd’s Airstream, parked on the empty slab where the diner once stood

FLOYD

I guess we need to get the word out. (cough)

FRED

Yeah, but advertising costs money.

FLOYD

I wonder how much we can get for the scrap aluminum from my dad’s plane. (cough)

FRED

I don’t know. (beat) But I guess we’ll get to work on it in the morning.

They both smile. Not big, but real. The kind of smile that’s earned in inches, not miles. The OPEN sign hums quietly above them as the last of the sun disappears behind the mountains, and the desert falls into stillness.

FADE OUT.

INT. VA OUTREACH KITCHEN – PALM SPRINGS – MORNING (1989)

SCREEN OVERLAY: “One Year Later 1989”

The kitchen bustles with quiet purpose—scrambled eggs steaming on trays, toasters humming, metallic clatter of utensils. A handful of veterans sit at folding tables, talking softly, eating slowly. FRED, now more settled, wears an apron and stacks clean plates with practiced rhythm. His hands move with purpose, but his face carries a shadow.

Beside him, the manager—JANINE, early 30s—scrubs a tray of mugs and glances over.

JANINE

We appreciate you still coming down to lend a hand. How’s Floyd doing?

Fred pauses. Not long, but enough.

FRED

It’s progressing. (beat) He’s getting weaker. Doctors say it’s moving faster now. Lungs mostly. Some days he’s got strength to walk the yard, others he doesn’t get outta bed. I moved his trailer up on the hill next to mine so I could be closer if he needs me.

Janine nods softly, returning to the mugs. Fred keeps talking, more to himself now.

FRED

He doesn’t complain. Still cracks jokes. Still asks if the OPEN sign’s lit every night. (beat) But… he knows. We both do.

Fred sets the last plate on the stack and wipes his hands on a towel. He looks out through the kitchen window, toward the setting sun and distant mountains.

FRED

He built that motel like it was the last good thing he’d ever do. Maybe it was. But it mattered.

A silence settles between them, gentle and full. Then Fred turns back to the counter and picks up the next tray.

FADE OUT.

EXT. ROUTE 66 – EAST OF AMBOY – LATE AFTERNOON (1989)

The desert stretches wide and empty. FRED’s 70’s Chevy pickup rattles down a sun-bleached stretch of Route 66, a tarp loosely tied over boxes of supplies in the bed.

He rounds a bend and slows. Up ahead, a crooked “ROAD CLOSED” sign leans against a pair of orange barrels. Beyond it, the bridge is collapsed, broken by time and flood—a gash in the forgotten highway.

Fred mutters something under his breath, turns off the pavement onto a dirt trail cut by decades of tire tracks. He descends into a shallow wash, the tires kicking up soft sand, then powers up the far embankment. The truck creaks but makes it. He picks up a faint dirt path that leads him back onto Route 66 on the other side.

He turns right at a small wooden sign faded by time that reads OASIS PALMS 2 miles.

FADE TO:

EXT. SUNSET MOTEL – EARLY EVENING (1989)

A lone car is parked in front of the far end of the motel and the guest is on the balcony of the second floor watching the sun set to the west.

INT. SUNSET MOTEL – FRONT OFFICE – EARLY EVENING (1989)

A ceiling fan creaks overhead. The office is clean but weary—maps curling at the edges, faded postcards on a corkboard, a jar of hard candy untouched. FLOYD sits behind the desk, thinner now, oxygen tank resting beside him. A lit cigarette trembles between his fingers.

FRED walks in, dusty from the road, carrying a brown paper bag and two bottles of Coke. He sets them on the desk and glances at the cigarette, then away.

FLOYD

Any word on the bridge? Everyone headed east is turning North towards the I-40. (cough)

FRED

Same story. State’s outta money, or interest. We’re not even a detour anymore.

Floyd takes a drag. The silence lingers, just long enough to turn heavy.

FRED

You really oughta quit that, you know. The smokes.

Floyd doesn’t look up.

FLOYD

And you oughta mind your own business.

Fred says nothing. Just stands there.

FLOYD

If you don’t like the way I do things, you can get the hell out.

The words hang in the air like ash. Even Floyd regrets them the second they leave his mouth. But he doesn’t take them back. Fred just nods once. Not hurt, not angry—just something quieter. Something settled. He walks over to the door, opens it, and pauses before stepping out.

FRED

You want anything from the store in the morning?

FLOYD

Nah. I’m good.

Fred exits, the screen door creaking shut behind him. Floyd stares at the smoke curling toward the ceiling, his hand trembling slightly. Outside, the OPEN sign buzzes faintly in the window. No cars pass by.

FADE OUT.

EXT. SUNSET MOTEL – LATE MORNING – SPRING (1990)

SCREEN OVERLAY: “One Year Later 1990”

The sun is high, but the air is crisp with a spring breeze. The SUNSET MOTEL sign—whitewashed and sun-faded—is halfway through a fresh coat of orange and gold. FLOYD, sleeves rolled up, stands on a short ladder, paintbrush in hand. He moves slower than he used to, but his hands are steady. There’s color in his face, and a spark in his voice.

FLOYD

You sure this orange ain’t too loud?

FRED

In this town? It’s the only thing louder than the silence.

They both laugh—the kind of laugh that comes easy today.

FLOYD

Did you pick up the mail in Amboy today? Anything important?

FRED

Nah, roads still closed and you got another letter from the county about the taxes.

FLOYD

Don’t worry—I’ve got the back taxes figured out.

FRED

It’s five grand, Floyd. You got a plan?

FLOYD

Buyer’s coming from Riverside next week. Said he’ll give me ten grand for the old backbar in the saloon. I told him its 20 feet long and my great-great-grandfather built it in 1885—solid oak. Still standing, even if the walls are falling around it.

FRED

That place hasn’t seen daylight in years. Want me to check it out? Just to be sure we can get it out of there?

FLOYD

I’m not worried. If we need to, we’ll bust out a wall and take it out across the old basketball court.

Fred nods, but he’s not as sure as Floyd is. Before he can say anything, a station wagon pulls into the lot—a young couple inside. Dust swirls as they park and climb out.

Floyd climbs down from the ladder, wipes his hands on a rag, and greets them with a welcoming grin.

FLOYD

You folks looking for a bed, or just admiring my fine brushwork?

YOUNG MAN

We heard this used to be a famous resort. Wanted to see it for ourselves.

FLOYD

You’re in luck. A commanding view of five historic buildings, one ghost town theater, and a gas station with an airplane sticking out the roof. All yours for twenty-eight bucks a night and a smile.

The couple laughs. The woman hands over cash as Fred grabs a room key from the office. Floyd watches them head toward their room, pride flickering in his eyes—alongside something quieter, harder to name.

FRED

You’re feeling good today.

FLOYD

Yep. Feeling real good. Taxes are sorted, and I think I got this health thing licked. (pause) Thinking I’ll go see the boys at the Kitchen this weekend. One thing’s for sure—you can’t keep a Smith down.

They share a look. Fred doesn’t answer, but his expression says he’s not convinced. Still, he lets it go.

Floyd climbs back up the ladder, brush in hand. The breeze catches the hem of his shirt. For a moment, he looks almost like the man he used to be—standing tall beneath the desert sky, signing his name back into the world.

FADE OUT.

EXT. PALM SPRINGS VA OUTREACH KITCHEN – MORNING – SPRING (1990)

The sun is rising over the low rooftops of Palm Springs. The VA Outreach Kitchen bustles with quiet energy—steam from coffee pots, the clatter of trays, a line of veterans already gathering outside the door.

An 80’s Chevy pickup truck pulls into the lot and parks. FRED hops out first, walks around, and opens the passenger door for FLOYD, who steps down carefully, slower than he used to—but with a smile on his face and light in his eyes.

FLOYD

I could’ve driven myself, you know.

FRED

Sure you could. (pause, gently) But I figured I’d come along for the company.

FLOYD

We didn’t have any bookings this weekend. The Sunset can survive a day without us. We can do more good here today, it’ll be good for us too.

Fred helps him straighten his jacket. Floyd adjusts his red Mobil baseball cap—faded and sun-worn. Together, they walk up the ramp and through the front doors.

INT. VA OUTREACH KITCHEN – MOMENTS LATER (1990)

The scent of eggs and coffee hangs in the air. Volunteers prep trays and stir pots. A few vets look up as the door opens—and then smiles start to bloom across the room.

JANINE

Floyd! Holy hell, look at you!

OLDER VET

Thought you’d gone and bought yourself a beachfront somewhere.

Floyd laughs, pulling off his cap.

FLOYD

I tried. Turns out all I got was a broken neon sign and a parking lot full of tumbleweeds. No beach, but boy do we have sand.

Laughter echoes across the room. People come up, clapping him on the back, shaking his hand. Someone brings him coffee without asking. There’s warmth here—real, earned, and deep.

Fred lingers behind, watching the scene. Floyd looks younger than he has in weeks. The VA kitchen is buzzing, and for once, so is Floyd.

FRED

You’re a damn local celebrity.

FLOYD

Just a guy with time on his hands and my mom’s award-winning chili recipe.

They head for the serving line, side by side. Behind them, the morning sunlight floods through the window. For now, the moment is good.

As Floyd and Fred settle into the rhythm of serving, JANINE stands off to the side, opening the day’s mail. She pulls out a letter, reads silently. Her smile fades. Floyd notices. Wipes his hands and walks over.

FLOYD

What’s wrong?

JANINE

(sighs) We’ve known it was coming… but this is it. This building’s been sold. Our lease is being terminated at the end of the month.

FLOYD

Jesus. Where are you moving to?

JANINE

We looked, but nothing we can afford has a commercial kitchen. (beat) To renovate even a small one would cost thousands we don’t have. So… we’re shutting down.

FLOYD

Thousands?

JANINE

Over five grand.

Floyd looks around the kitchen. At the food being plated. At the volunteers. At the men and women eating quietly at folding tables, like they do every morning. The hum of life continues, but a heaviness settles in his chest. He glances at Fred, who has heard everything and just gives him a look.

FADE OUT.

EXT. SUNSET MOTEL – LATE AFTERNOON (1990)

FLOYD and FRED pull into the lot of the Sunset Motel, still buzzing from their visit to the VA kitchen. But the moment fades as soon as they see it. The front office glass doors are shattered, splintered glass glinting in the sunlight. Spray-painted graffiti scrawls across the white stucco walls—random tags, profanity, a crude smiley face dripping red.

All the room doors stand wide open, swinging in the wind. Fred jumps out of the truck, heart pounding, scanning the damage.

FRED

No—no, no, no…

He runs to the nearest room, peers inside. The bed is still there, mattress stripped. The air conditioning unit is gone. He checks the next. Same. All of them.

FRED

They took all the damn A/Cs. Every one of them!

Floyd steps out of the truck slowly. He surveys the wreckage, his face unreadable. Not angry. Not shocked. Just… still.

FLOYD

I guess they needed them more than we did. (beat) And a fresh coat of paint never hurts.

He walks toward the shattered office doors, glass crunching under his boots. He picks up a shard, studies it in the light, then lets it fall.

FLOYD

Just wish they’d left the office alone. Guess we’re going with plywood doors for now.

Fred stands in the doorway of one of the rooms, hands on his head, breathing hard.

FRED

We can’t keep doing this, Floyd. We’re barely keeping the lights on as it is.

FLOYD

I know.

Floyd steps inside the office, stepping over the frame. He reaches behind the counter and flicks the switch. The neon OPEN sign buzzes faintly, then dies.

He stares at it for a long moment. Then turns to Fred with a tired half-smile.

FLOYD

Well. We were due for a remodel anyway. Hopefully, the guy from Riverside comes through next week.

Fred doesn’t laugh. He just watches his friend, worried more by Floyd’s calm than by the damage itself.

FADE OUT.

EXT. SUNSET MOTEL – LATE MORNING – A FEW DAYS LATER (1990)

A brand new metallic silver pickup truck pulls into the parking lot, behind it a massive white moving van. Dust kicks up as the polished wheels crunch over the cracked surface. It gleams like something from another world.

FLOYD and FRED step out from the motel office, wiping their hands on rags. Floyd’s shoulders are thinner, but he walks tall.

The PROP BUYER, late 40s, city tan and aviators, climbs out of the cab. He squints at the sun, then at the worn buildings around him.

PROP BUYER

Jesus, this road is a nightmare. GPS had me detour through a wash—thought I was gonna lose the truck.

FLOYD

That’s just Route 66 saying hello. She don’t make it easy.

The buyer wipes his forehead with a cloth and looks around.

PROP BUYER

So? Where’s the back bar?

Floyd lifts a hand, pointing down the slope toward what’s left of downtown. The old saloon stands like a husk, roof partially collapsed, shadows in the doorframe.

FLOYD

Right there. Just waiting for you.

The buyer stares at the structure for a long moment.

PROP BUYER

What the hell? How are we supposed to get it out of there?

Fred smirks, already grabbing gloves and motioning toward a wheelbarrow and a pry bar in the back of his truck.

FRED

Follow me. You bring the check, I’ll bring the miracles.

Floyd doesn’t say anything—just watches the light shift on the roof of the saloon, like time peeling back a layer.

FADE OUT.

INT. OLD SALOON – DOWNTOWN OASIS PALMS – LATER (1990)

The front doors creak open, and light floods the dusty gloom. The air is thick with rot, dry wood, and memories. Chunks of tin ceiling hang down like old lace. The floor is buckled, covered in broken lath, caved-in beams, shattered bottles from another lifetime.

But at the far end of the room, untouched by the decay around it, stands a magnificent oak back bar—a masterpiece of 1885 Western craftsmanship. It rises nearly twelve feet tall, dark-stained oak with hand-carved corbels, fluted columns, and an arched mirror backing now coated in years of dust. The lower cabinets are still intact, brass handles worn smooth by a thousand stories. Etched glass panels gleam behind the grime, catching just enough light to reveal their designs—grapes, stars, and vines, bordered with delicate filigree.

A ghost of music and laughter seems to echo off the old mirror.

A ghost of music and laughter seems to echo off the old mirror.

PROP BUYER whistles low, hands on hips.

PROP BUYER

Now that’s the real deal. Jackson is going to go nuts for this.

He steps closer—and stops. Between him and the bar is a wall of debris: collapsed joists, chunks of brick, half a rusted stove, and three feet of rubble.

PROP BUYER

Are you kidding me? It’s trapped. (beat) You got a jackhammer? Skid steer? You’re gonna need ‘em.

Floyd and Fred step forward, assessing the mess.

FLOYD

That’s why it’s still here. God dropped this building like a time vault. You can get it out.

PROP BUYER

Here’s the deal—if I have to bring my crew and pull it myself, I’ll give you $5,000. Not a dime more.

FLOYD

That’s half of what we agreed on.

PROP BUYER

Then clear it yourself and get it outside ready for pickup. If I gotta come back next week, I’ll give you $7,500. But if my client in Santa Barbara doesn’t have it by Thursday, he’s going with a reproduction out of Burbank. (beat) I don’t care how old it is. If it’s scratched, chipped, or late… no deal.

Silence. Dust motes drift in the light. The back bar glows in its alcove like a cathedral relic buried in ruin.

FLOYD

Well… She’s waited this long. What’s one more week?

FRED

Floyd… we don’t have the equipment. Or the manpower. If we need to dig that thing out ourselves, it’s a month of work—minimum. (beat) And that’s if it doesn’t kill us first.

Floyd runs his hand gently along a carved edge, brushing away a century of dust. The grain shines beneath his fingers.

FLOYD

Fine we’ll take the five… and take your bar.

Floyd turns without another word and walks out, his boots crunching over broken glass and plaster. The buyer and Fred exchange a glance, unsure whether what just happened was surrender… or something else.

FADE OUT.

EXT. CLIFFHANGER TRAILER PARK – SUNRISE – Following WEEK (1990)

The desert sky is barely blue, the first light of dawn stretching long shadows across the lot. Everything is still—until the sudden rumble of an old pickup engine breaks the silence.

FRED jolts awake in his trailer. Still in his underwear, he stumbles to the window, blinking hard. Outside, FLOYD is behind the wheel of his father’s old red truck, the AIRSTREAM hitched and idling, dust swirling around the tires. Fred bursts out of the trailer barefoot, shirtless, heart racing.

FRED

Floyd! Where the hell are you going?

Floyd doesn’t look at him—just keeps his eyes on the road ahead.

FLOYD

I’m going back to Slab City. (beat) I’m done here.

FRED

You get some money and now you’re just running away? What about the taxes? What about fixing the Motel? What about your family’s oasis?

FLOYD

Fred, you’ve been a good friend. You keep your trailer, hitch it up to your truck, and take it somewhere nice. Let the state have this sand pit. I’m done.

He puts the truck in gear. The tires crunch over gravel as the Airstream follows, silver catching the rising light. Fred stands alone in the lot, dust brushing past his ankles. He doesn’t yell again. Just watches in stunned silence as Floyd drives away, the OPEN sign still flickering behind him in the motel office window.

FADE OUT.

EXT. CLIFFHANGER TRAILER PARK – MOMENTS LATER (1990)

The rumble of Floyd’s truck fades into the morning silence. FRED stands barefoot in the dust, still staring down the road, stunned and hollow. He turns slowly and walks back toward his trailer. The light is soft now, creeping across the mailboxes.

Fred notices something—a yellow envelope tucked into the rusted mailbox by his door. He pulls it out. It’s unsealed. Inside: a check made out to “CASH” for $5,000, already endorsed on the back in Floyd’s shaky handwriting. Fred unfolds a short note scribbled on the back of an old motel guest receipt.

FLOYD (V.O.)

Give this to the Kitchen. Or keep it if you want. Others need it more than I do. —Floyd

Fred lowers the paper slowly, staring at the check. His eyes shine, but he doesn’t cry. He just stands there in the pale desert light, wind tugging at the corner of the note, the motel silent behind him.

FADE OUT.

EXT. SLAB CITY, CALIFORNIA (1992)

SCREEN OVERLAY: “Two Years Later – 1992”

The sun hangs low over Slab City, bathing the endless desert in hues of orange and gold. A scatter of makeshift homes—trailers, tents, and shacks built from salvaged scraps—dot the landscape. Dust swirls in the warm wind, coating everything in a fine layer of grit.

FLOYD SMITH, now 47 but looking closer to 80, slumps in a weathered lawn chair beside his faded, sun-bleached Airstream. His skin is leathery, hair long and wispy, shoulders sunken. A cigarette burns between his fingers—forgotten.

Across from him, a YOUNG TRAVELER in his mid-twenties perches on an overturned crate. A battered backpack rests at his feet. He listens intently, eyes fixed on the old man like he’s hearing scripture.

FLOYD

(mid-story, shaking his head) So the quake hits, and just like that—boom—half the town caves in on itself.

He finally takes a slow drag, exhaling toward the dying sun.

FLOYD

(chuckling) Hell, I should’ve seen it coming. But I was too high to do anything but watch.

The traveler leans forward, captivated.

YOUNG TRAVELER

So what happened to Oasis Palms?

FLOYD

(low, distant) Water dried up. Route 66 shut down. Now the Barco Plateau’s under six feet of sand—like it never existed. Hundred-fifty years my family held that land… and they’re still fighting over the water.

YOUNG TRAVELER

Are you serious? Or are you just… making this up?

FLOYD

(smiling faintly) Like my friend Jimmy used to say— It’s a semi-true story, believe it or not.

He coughs—a deep, hollow sound—but waves it off.

YOUNG TRAVELER

(softly) So… that’s it? That’s how it ends?

Floyd smirks. Takes a last drag, then flicks the cigarette into the dirt.

FLOYD

(grinning) No, kid. It don’t end. Not ‘til the last one of us is gone.

FADE TO BLACK.

EXT. OASIS PALMS – SUNSET (1992)

FLOYD’S old red pickup rolls slowly into the ruins of Oasis Palms. Dust billows behind it, golden in the last light of day.

He parks in the middle of what was once the town square.

He parks in the middle of what was once the town square.

He climbs out slowly, thinner than ever, moving like a man made of memory. He passes the dry, crumbling fountain, where his great uncle once stood guard over the town. A rusted plaque lies face-down in the sand.

He walks to where the old saloon once stood—now a collapsed shell of wood and brick. He kneels in the rubble, brushing debris aside with tired hands. His toe strikes glass. He digs deeper and pulls free a dirt-covered bottle of Old No. 5 and a single shot glass, still intact.

Bottle in hand, he walks slowly down the remains of Main Street. The Sunset Motel looms ahead—gutted, looted, a hollow skeleton of what it once was. Doors hang open. The neon sign is long dead.

Floyd doesn’t stop. He walks past the motel, toward the church ruins, barely recognizable now—just foundation stones and a twisted iron cross buried in brush.

He climbs the hill behind it, reaching the old graveyard. Rusted fencing surrounds rows of sun-bleached headstones, some tilted, some broken, many weathered beyond reading. Floyd sits among them, breathing shallowly, taking it all in—the spirits of his people, the land, the silence.

He opens the bottle. Carefully, reverently, he pours a shot. He sets the glass on the grave of his great-great-grandmother, Malika Smith.

Then, he drinks straight from the bottle. Whiskey dribbles from his chin, splashes into the dust. He drinks until the bottle is dry.

The wind quiets. Floyd leans back against the earth. Eyes closed. One final breath.

FADE TO BLACK